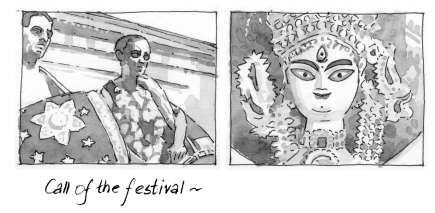

Durga pooja, the festival montage.

There have been two references to Durga pooja so far. Harihar had promised a new wrapper to Pishi at the festive season and the children had been asking each other about it. “Twenty one days,” Durga had told Apu the day she got the beating. Finally the day has arrived.

The last chapter ended with Pishi landing up at Raju’s door for shelter—a personal tragedy, underlined by the rustic folk melody associated with that ‘ancient’ character. Over the fade the music changes to a complete switch of mood—from soft, solo, individual-associated, bowed instrument to a loud, orchestral, festival-associated, percussion. From personal to public, so to speak.

Notice the structure of the montage.

The first two shots not only establish that it is the festival of Durga pooja but also its ‘beckoning’ tone. Literally on the beat of the drum, you might say. What they do not readily establish is that the call is being issued from Sejo-bou’s courtyard and duly reaching Apu and Durga’s. That is gradually introduced by the momentum of what follows and is in due course confirmed with her distributing sweets.

As in many ways before, even the festival is a reiteration of the one way traffic between the two households.

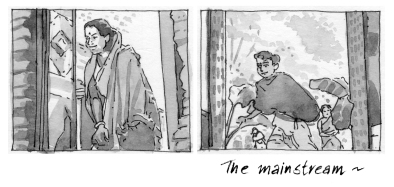

Notice the dynamics of mise-en-scene of this third shot where children rush out to join the fun.

It’s a low angle static through the courtyard door, a familiar view wherein Sarbojaya sits adjusting Apu’s clothes. The instructions to Durga are to enter the frame running from inside, going past Apu and rushing out through the door. The task assigned to Apu is to look out for Durga and just follow her. It’s entirely for the mother to convey the festive cheer through rising after him trying to tuck in whatever part of his new dress and come laughing up to the threshold. The camera has to just tilt up to adjust for Sarbojaya. That’s the shot.

Given these broad parameters and one rehearsal, there’s no way the shot would not work in just the first take. Like many other shots, which finally are used silent, this one too has been staged and taken with full sound component to ensure the ease and facility of the actors. Almost certainly, Sarbojaya has been asked to independently work out with Apu as to what of his dress she has to be tucking and Ray only asks modifications if necessary after watching the rehearsal.

Talking less is the trick, it would seem. Trying to describe elaborately in words, as new directors tend to do—the expression, motivation and what not—gets to be a nuisance for the actor. Done aloud or quietly, such an approach must essentially betray lack of confidence on the part of the director.

Even otherwise, Ray does not direct the world, he merely directs his own way of looking at it.

The next shot also is a low angle, through a wider and more affluent door—presumably Sejo-bou’s—but with the camera pan and tilt firmly locked.

This ensures a more generalised rendition of the children, of whom now Apu and Durga are merely one part. Also, the shot is slightly under-cranked—16 frames or so per second—for another degree of abstraction through a mild caricature. (This should not be mistaken as a casual thing to do; in pre-digital times such a shot would need a change of motor of the camera.)

Normally under or over-cranking is used for broad effects of the slapstick variety or of the dream-like, floating movements, both of which Ray used extensively in his filmmaking. In addition he also used a whole range of middle shades of camera speeds for more nuanced effects. The present case of under cranking, for example, would be a rather unorthodox use of the device to slightly pep-up the sequence, just to add a touch of the sprint to it. A more noticed and commented upon use of the other variety, over cranking, is to be found in his 1984 Ghare Bahire where early on in the film Bimala sets aside tradition and steps out among the men in the parlour.

Notice, too, that Apu and Durga appear in the shot after a clear break. This enables us to see and recognize them from afar. There was no such chance if they had been among the first group of children.

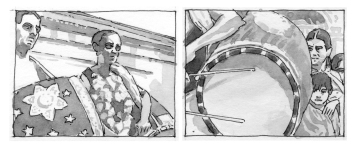

Sejo-bou is distributing sweets.

Once again the children have been collected on the promise of distribution of sweets, which have been actually brought in once the camera and microphone are ready for the shot. Only Sejo-bou, Durga and Apu’s positions have been fixed and care has been taken to have all the children taller and bigger than Apu so that he’s lost among them in the first shot in order to necessitate the second. It’s quite possible that Apu was held back from the first shot altogether.

A touch of embarrassment on Durga’s face while collecting sweets actually comes from her having to join smaller children for the shot rather than from having to collect them from Sejo-bou.

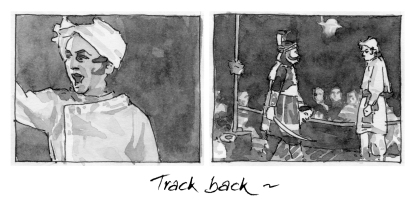

Back to the drummer.

With this shot the montage comes round a full circle back to the drummer.

Like any other recurrence in Ray, this too is one with a difference. While both are low angle shots, the opening shot of the montage has a longish track alongside the drummer—the much decorated chest and all—whereas in the last shot the drummer comes over showing his beating drum to a static camera and finally occupies the whole screen. Through what lies ‘bracketed’ between these two shots, the montage starts with introducing the fact of the festival and ends with giving a feel of its overwhelming quality.

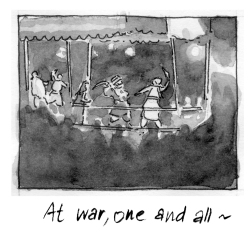

The jatra performance.

The drums over, note that the opening shot of the performance establishes the principal characters, the essential conflict, visual motifs and the general range of image sizes going to be deployed in this staging.

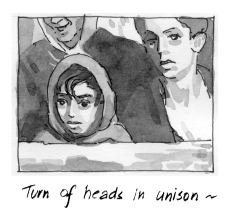

The audience is already in evidence in the first shot but the second shot picks out Apu watching from behind the barricade. Also introduced through exaggerated movements is the level of audience participation as well as the boy’s up front position.

With these two shots, all the visual elements of the theatrical act have been introduced.

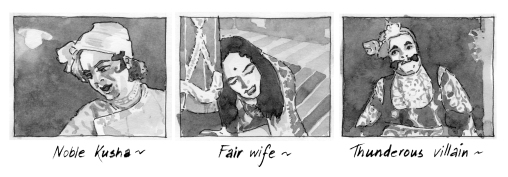

The piece being staged is a remote sub-plot from the tail end of Ramayana and involves the younger son of Lord Rama, Kusha, who is dressed here in white. Though the episode itself is highly unfamiliar, the pitch, the scale and the manner of presentation is widely known and enjoyed all over the sub-continent. The issue presented here is the dharma of a woman who is torn between her love of the father and duty towards her husband. (Or is it the other way round?) Eventually she passes the husband a sword and urges him to defend himself again her father and brother.

The next round of compositions are a closer view of the high players—the valiant Kusha with his painted side burns, the fair wife who is clearly a man and her evil brother who makes a thundering entry from the sides. Apu clutches at the barricade and sit up sucked into the action.

While Ray is having a go examining a folk play with the tools of the cinema, it’s touching to visualise how innocently and with what dedication each of these actors—in 1954—were trying to help, literally putting their best foot forward for “film shooting”. And they certainly aren’t caricaturing either—jatra acting seen through the cinema’s photographic realism is caricature.

On the other hand, the joke would be upon Ray if the rest of his depiction of the story would be anything but stark realistic.

Notice that all the shots of the players are generally taken from the low angle viewpoint of the spectators and those of the spectators from the high angle of the players. The only exception is the toppish angle of the wife clutching at her father’s feet, which, since it is in response to an intense address by the husband, takes on his subjective view.

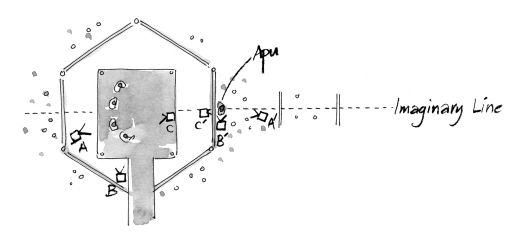

Where exactly is Apu sitting in relation to the performance?

On a casual viewing the impression comes that he is perhaps among that section of the audience who we first see at the end of the establishing shot and that the second shot showing him behind the bamboo barricade is most likely a match cut along the same axis. But a close scrutiny of his direction of looks vis-à-vis the evil brother’s entry reveals a bit of a mix up. And probing deeper you notice it to be a forced matching. The humour of the inter-cut helps to tide over what is inherently a problematic situation.

Apu is in fact sitting facing the action and even though a jatra performance is addressed to audience sitting all around the stage, for this scene Ray has conceived it to be played for Apu. Thus the performance we see in the film is all from Apu’s viewpoint because ultimately the value of the scene is purely in terms of the effect it has on him. Therefore the quality of his involvement is a key consideration in realising this scene.

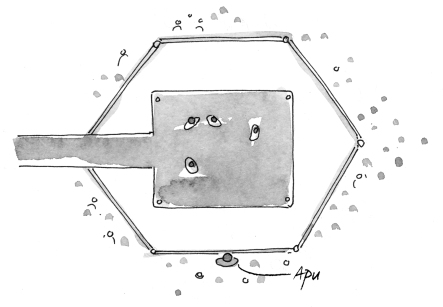

The principle of Imaginary Line tells us that as long as the camera positions are kept on one side of the line, the shots will all cut well and the relative geography of the scene would be faithfully represented on the screen. This would be too bland a formula to be artistic by itself. But a more nuanced application can throw up immense creative possibilities and at extremes it can even pose serious artistic dilemmas. For example, in portraying an interaction between the two given stationary positions three sets of camera angles represent the broad range of possibilities: AA’ which would cover the action from the over-shoulder position, BB’ which will present an interaction of pure profiles and CC’ which will provide a near frontal, least mediated and most intensely subjective view of the characters vis-à-vis the situation.

What will happen if CC’ camera positions are shifted to be actually on the Imaginary Line? Being on the line is strictly speaking not observing the line but that is the position where both the participating subjects are optimally oriented to each other, looking into the lens in order to be looking at each other. Furthermore, being on the line in this situation provides yet another expressive dimension to Ray—since Apu is supposed to be sitting right in front, his switching from player to player can be realistically exaggerated for a valid touch of humour. This he does by making him look screen left to screen right in order to represent his turning attention from the speaking noble Kush on the right to the thundering villain entering from the left.

The resulting mix up in screen direction has to be the inevitable consequence of violating the line but Ray chooses to pay the price for gaining uncompromised authenticity on Apu’s involvement in the performance. By staying on the “right” side of the line, there would have been no confusion whatsoever on the geography but Apu would certainly not look all that submerged and absorbed in that grand spectacle.

Straining and stretching the Imaginary Line in this manner occurs in Satyajit Ray again and again. Sometimes he adds other elements making the application further complex. Always, as it must, geographic clarity takes the beating but he is always ready to pay the price.

In Shatranj Ke Khiladi (1977), he has the two players playing chess throughout the film. The last game is played in the open and in the falling light of the evening and for that the camera is again on the line and a little high so that each player comes to have an obliquely lit bare ground immediately behind him. Furthermore, each composition has the player in the middle of the frame and both of equal size. And the shots inter-cut at the peak moments without variation and for quite a while.

As can be seen, it’s against all principles of good cutting but Ray is fascinated with the concept and pushes it regardless. And on his graduated scale of application this defiance charges the image with a level of abstraction not otherwise possible to achieve.

For the third and final round of treatment of the performance, the view cuts to the longest shot of the situation and holds uncut until the end of the sequence.

Essentially this view provides a more objective look at the activity as a whole, giving equal emphasis to the players as well as the spectators, making it look even more absurd with everybody holding a sword and fighting everybody else. Not only is it a winding up of the scene, it’s passing a judgment as well.

Is jatra a new idiom being introduced for the first time in the film?

To be sure, nothing new is ever introduced in good narrative cinema until so late: it has to be a variation of one or the other strands introduced earlier. Jatra has been talked about by Harihar in terms of writing an original piece right at the end of chapter I. Next the subject is taken up in the grocer-teacher scene at the level of organising a performance in chapter 2. And again in chapter 4 Harihar mentions a new plot buzzing in his head. As it happens, it’s another mythological Vibru-bahan, a sub-plot this time from Mahabharata.

On another plane, jatra performance is a growth of Pishi’s story telling—both are performances and both have a strong appeal for the children. In the same way, all other kinds of entertainment integrated in the film, standard or improvised, would fall on this plane.

Secondly, notice certain structural details from the mise-en-scene.

One important component of jatra is the presence of live musicians who provide their highlighters and under liners from a position below the stage. But they have not been visually represented in Ray’s treatment here. The scene being principally about the impact it makes on Apu, showing musicians would have been a digression, a distraction. The music, however, is heard simmering and swelling at appropriate points.

And finally, note the visual “pegs” used in the scene, namely the hanging lamp and the horizontal barricade.

Both these had been first established at the end of the opening shot as visual motifs in an otherwise sparse setting, and both continue to be used as visual references throughout the rest of the scene. These essentially have the effect of “binding” the scene together.

The jatra over, home, Apu dons the moustache and the crown.

Notice the clumsiness of the operation in a firmly composed and clearly established mirror shot. Again, the child actor has been given a whole task to do—fix the moustache and tie the crown—without abandoning half way through. Thus when the moustache slips by the time he gets to the crown, it passes off as a typical childlike gesture.

Mother returns home calling children, Durga returns from her wandering and after their three-way scuffle in and out of the house, both children are sent off to look for the missing calf.

Most shot compositions are “recalls” from earlier usage, from the Durga-beating scene. The reason probably is to neutralise those grim associations in this humorous context and in the process also blend the patched porous corner securely into the house set. Mother returns calling Apu and Durga just as we saw her doing the day he was sent to school. (The two shots may well have been taken one after the other.) The shot of mother doing Apu’s crown uses the same through-the-door idiom as used when he had approached father, asking coins in the sweetmeat seller sequence. Durga’s entry into the house remains through the same arch as seen in the earlier scene just before being thrashed and so does the children’s chase through the same structures as had been used to show her being beaten and thrown out of the house. Even the vertical telephoto tilt from the scuffle to the oncoming mother is familiar from the earlier mother-Pishi tiff from the last chapter.

Likewise there is an interesting reversal. Having so far been followed everywhere by Apu, Durga is for once chasing him in and out of the house. This temporary reversal only serves to emphasise the normal, which both children return to as they patch up and go looking for the calf.

Setting up the chase, children have been given the task to really run and catch each other while the camera stays firmly composed. Reasonably the shot would have to be repeated twice or thrice until Apu gets pinned down at the desired spot outside. Considering further development of the scene, anywhere else would be NG, no good.

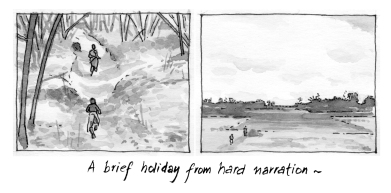

The children going away looking for the calf is suddenly an extended treatment covered over three, rather lengthy, long shots.

It’s quite a while since the story came upon a leisurely stretch and coupled with the theme music takes on a contemplative complexion. Also, it provides for a momentary relief before resuming on another dark passage.

Notice the path that the children take while running away from the camera in the final shot. Whereas the tilt up is an uninterrupted continuous action, following the field’s embankment the children take a brief left turn before resuming straight. If he meant to avoid this, another stretch could be chosen that provided for a continuous straight run or else the camera could be instructed to “follow” them, but neither option has been exercised. Again as many times before, camera is not a slave of the action but rather an ‘input’ to bring out the complexity of the moment.

From the children going “outward”, Pishi approaching to enter. Inward.

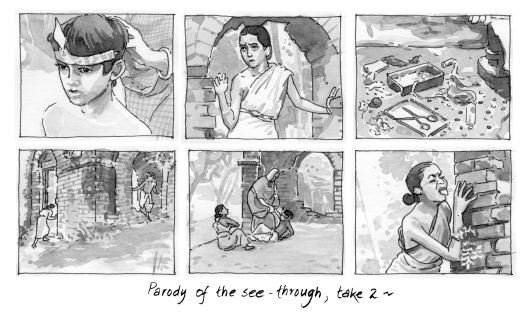

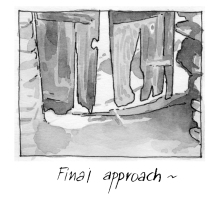

From open air, clear day, outdoors—dissolve to—an age ravaged, see-through, courtyard door. A new sound announces the arrival of an old, familiar character. It’s Pishi, now using a stick to walk. And the door, not only does it look old, it also rattles; which is what Sarbojaya hears of Pishi entering.

Most likely it’s a specially treated door for this shot. Or else, the shot may even be cheated from another location. The decay of the door is important since it echoes the decaying old woman besides much else. The rest of the scene too deploys many other devices to enrich this on-the-brink image of Pishi.

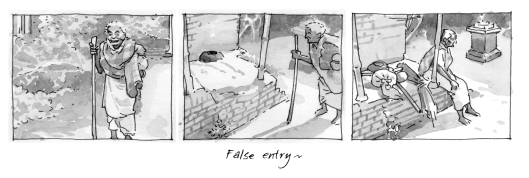

Examine Pishi’s entry after clearing the door.

She walks past the shrubbery before taking the bamboo post. The action is covered in two shots, wherein she exits left in the first shot and enters right in the second.

Technically this should cut smooth and it does, but action wise her turning round the corner has remained unaccounted for. Pishi’s entry in the bamboo post composition, therefore, appears for a moment amiss. A match cut needs to account for the turn around the corner whereas a clear entry into the frame can imply that turn.

Under the circumstances, Ray had two options. Either build in another of Sarbojaya’s shots in between the two shots—a cut away—or at the time of shooting go for a tighter composition for the bamboo post shot, taking care to exclude the corner, so that making her enter the frame would imply the corner cleared. (Simply panning the camera left to have an off-center composition would look forced and not belong to this film.)

To my mind, Ray chooses to retain this momentary infirmity for schematic reasons. Once Sarbojaya has been introduced eating in the kitchen, the scene stays with Pishi through her misery and visually comes to the housewife only when the old woman approaches her for water. Bringing in Sarbojaya too often would dilute Pishi’s misery.

Likewise, the reason that the composition is not tighter in the bamboo post shot is again for schematic reasons. In view of the unique importance of Pishi’s veranda at this stage of the story and its comprehensive portrayal—this is after all her final departure from this house—the view is going only successively closer. The first shot of the place therefore has to be a wider, introductory view rather than a tight one, which has been kept reserved for later. Also the visual impact of her worldly belongings as she drops them on the veranda, would go missing in a tighter composition.

A one-shot cut away to the children.

Notice the highly unusual composition in the static frame. Against clear sky, Durga sits chewing a sugarcane stick as Apu appears at the bottom of the frame. Seeing him Durga exits while the boy hurries to take the same space and goes after her. This is the regular Durga-leading-Apu-following idiom.

Notice the deployment of burnt out patches of sun over the courtyard floor.

It is hot sun as the scene is taking place and that adds to the misery of the old woman. In contrast Sarbojaya sits in the shade of the interior, her kitchen.

The sun patches peak in the shot where Pishi breaks into a smile, looking at Sarbojaya.

The beauty of the shot defies description. An ancient, bronze look contrasted against featureless burnt out patch of sun. She already resembles the ghost of her narration to the children a while back. Music beginning here underlines the moment.

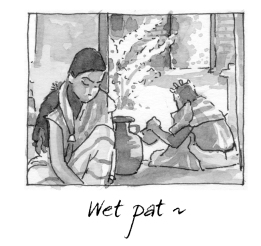

Soon after, another play on the patchy sun occurs when Pishi pats water on her head.

The fine spray is seen against a shaded area in the long shot. Cutting to a closer view for emphasis would be ruinous and is avoided.

Notice the extent of Sarbojaya’s help towards letting her have the water—she just takes the lid off the pitcher, leaving the rest for Pishi to do. This gesture of ever so slight softening on her part serves as a bridge between her cold indifference so far to her expression of remorse a shot later as Pishi finally leaves. This range of emotions, even though looking a bit forced, sums up Sarbojaya’s attitude towards Pishi in Pather Panchali.

In one of his articles Ray says that he was fascinated by these two contrasting aspects of Sarbojaya’s character from the book, the cruel and the compassionate. But the two emotions cannot remain going parallel all the time; for them to be convincing in a character, there has to be a moment where the two meet and merge for a switchover. Remorse on the housewife’s part as Pishi is turned away is that moment of merger, followed by the switchover to clear sorrow when she eventually dies.

The only other time Sarbojaya ‘helps’ Pishi is upon Apu’s birth. Eyes welling with emotion, the old woman asks her to show the baby’s face and Sarbojaya obliges. Notice the extent of that help—minimal—in terms of Sarbojaya’s action of adjusting the quilt around the infant’s face.

Notice that after all that struggle, Pishi drinks much less water than she pours on the plant.

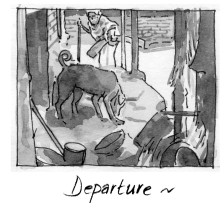

Notice too that Pishi’s final departure is not shown through the courtyard door but down her veranda.

This has been a key composition associated with her life in this house—she cooking, Durga sitting by the post, Sarbojaya fuming. In place of all that liveliness, already there is neglect and decay; already a dog is sniffing around. This is Pishi signing off, so to speak.

A word about the pattern of intercut between developments at home and the exploits of the children. Seeds of such an intercut had been sown early in the film when an angry Pishi had first walked out of the house. Durga had then returned just in time and tried to stop her. Again in between Sarbojaya drove her out on the issue of the wrapper and the children then were playing picnic under the trees. This time round as Sarbojaya is again being cruel to the defenceless woman we miss the children, Durga in particular. That is what the first cut away shows in the present sequence—a carefree Durga chewing sugarcane far, far away.

On the strength of that cut away, a whole scene has now been developed. As Pishi has been driven out at home, children are far away playing, learning, growing…

[To be continued]