The ‘purpose’ of the travel-montage—Sarbojaya’s smile—over, the view dissolves to a shot of their new village before it dissolves to them arriving in their new house.

Notice this rather ‘invisible’ shot. It’s supposed to be bridging the two specifics, a filler of sorts. It couldn’t be done without and it has to have a non-specific character.

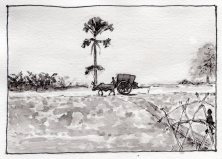

The shot has all this plus an introduction to what can be described as the outskirts of the Bengal village—waterways and all—where soon after this Apu is found on two-three occasions before he discovers the village school. Also, being a bank of the village canal, it provides an opportunity to have the boy run up and down to express his curiosity and interest in the school.

And not the least it maintains the water connection between their old home in Benares and the new one here. As it happens, their new house is also next to a pond, the same as in PP.

Notice that the family approaching the house passes by the pond and their reflection in the water—easy to manage if wanted—is avoided. That would be repeating what has already been done in PP, twice over, once in the sweetmeat seller sequence and less noticeably later when children run on both sides of a pond as Pishi stands bending still.

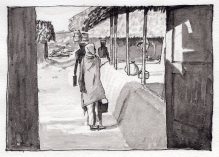

Interestingly, the main courtyard door as the family enters is wide open—there is nothing to lock here. Bhabratan’s room inside is locked though.

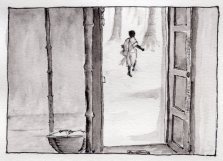

At the end of the film when Apu comes home looking for his mother, he enters the premises, goes back and forth across the courtyard and emerges completely unrestricted at the other end until realisation dawns on him that she may be no more. That indeed is the case.

Another see-through house after PP? Not only is the new house next to a pond, it’s also laid out on the PP pattern as we soon discover: courtyard, verandahs, mud-wall rooms. Why should it be so? Because it keeps echoing the old house for Sarbojaya as well as for us. In a subconscious then-and-now connection to the extent it works.

Notice that Sarbojaya being new to the place, there is no line given to Bhabratan assigning the room to her. She just settles down to what is there. Equally, of course, there is no word of thanks from her.

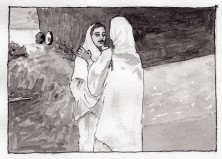

Overcome with emotion, Sarbojaya goes no further than the courtyard door and just sits in a verandah. Tired from walking? Facing uncertain future? She is back to being a widow, having a son to bring up by herself.

Notice the composition. With a part of her luggage in view and with her new place a little more in evidence through that window, it’s her room where Sarbojaya sits contemplating on her situation. And her life.

Suddenly, a train is heard. Apu who is already running up and down through the courtyard calls out excited.

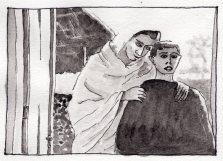

The mother joins the boy to see the distant train.

It’s a house with a rail-line attached!

The scene, while it introduces their new house, is also simultaneously designed in a symbolic mode. Barely have they unloaded when the boy discovers the train. He is fascinated but Sarbojaya instinctively sees it as a threat to take her son away from her. She comes from behind to claim him, literally putting her arm around the boy. Seeds of conflict are already sown in this key composition. She leans on him and he has a faraway look. But as the rest of the film goes on to reveal, she is on a losing ground. Soon the boy is going to be attracted to the school and insist on joining it over the priestly training that is started for him. And in due course he is going to be leaving to join college in Calcutta—and by the very same train—in full awareness that the act is going to leave them both miserable.

Ray famously described this as the boy “growing up and away from the mother”.

Thus, practically from the word go, the scene sets the thematic agenda of the rest of the film and proceeds accordingly. In this key image one can see the boy’s imagination fired.

Notice too that the route Apu takes through the house this first time is exactly repeated at the end when he comes home to discover that the mother is ‘gone’. This one is a subtle ‘plant’ for that future walk-through at the end of which he emerges from the house and sits down defeated and weeps. Defeated? Vanquished? No, because he gets up and take charge of his situation and life. He decides to leave for Calcutta, telling a surprised uncle that he would perform the necessary rites in Calcutta. Unvanquished! Aparajito!

In a highly understated irony of Aparajito, both Father’s last rites as well as mother’s eventually get to be performed on the banks of the sacred Ganga.

From the first day in the new house, to a new routine.

It’s a masterstroke of a transition from train to train on the horizon, which was the clock in British India that governed life in the nearby villages. A stray dog has materialised, live smoke indicates that the hearth is lit and Sarbojaya who now has another, much younger widow helping her around, already carries a ‘load’ of keys on her shoulder.

The family is once again now settled, so to speak.

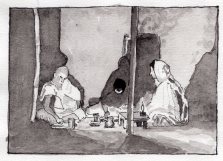

Night. Bhabratan and Apu eat by the lamp as Sarbojaya sits serving.

The elder-man announces he would be gone after a week, then asks Apu to join him from the next day to learn priestly rituals in that period. Notice the utter simplicity of the manner in which a major decision gets taken for the boy.

He pauses drinking water from the glass and turns to look to the mother; and the camera follows that look to find Sarbojaya smiling in approval. No discussions, no debating, just two shots. Notice that rather than ‘emote’ one way or the other, Apu has been given specific steps of action to perform, camera asked to pan at a certain pace and Sarbojaya told to respond through a smile.

How would the director judge the shot, particularly the camera operation, in such a situation? By simply looking over the cameraman’s shoulder as he did the job in conjunction with the actors performing, both viewed from an overseeing position. Notice that in this shot Sarbojaya waits a tad longer than ‘natural’ before breaking into her smile. And notice as well that strictly speaking, Apu’s look falters before the camera fully leaves him but is still accepted as OK for the action as a whole. Perhaps a second take was tried but found to have gone worse somewhere else and rejected in favour of the first. Holding the glass short and switching of looks has worked particularly well in the first attempt.

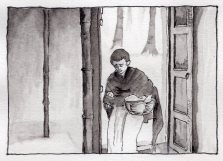

Apu’s training as priest is covered in three shots taken on a common concept and each dissolved into the next to imply progression.

Bhabratan gives the first instructions, then young widow Nirupama substitutes supervising and finally the boy performs on his own, right through until the chants and obeisance. Notice the boy’s sense of hurry when left alone. That would be typical of his age, as well as indicative of a degree of lack of interest in what he is being trained as.

As though to further the same idea, outdoor has been a constant presence through the door behind him. All along his training, the outdoor beckons, so to speak.

The door in the background is as deliberate through Apu’s training as was the absence of any such opening immediately after Harihar’s death in Sarbojaya’s new house where Bhabratan had come visiting. Ray’s cinema expresses both through inclusion as well as exclusion.

And it’s when he is outdoors that the contrast strikes us with the routine of life in the village.

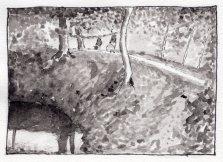

As Apu goes burdened with his priestly persona, children his own age go wildly chasing one another and rolling down the banks of the canal in gay abandon. Since this scene leads him to leave priesthood and join the village school, let’s examine the mise-en-scene in some detail.

Starting with carrying the deity’s idol and heavily wrapped in a priestly shawl, Apu already looks like a grown up when first seen walking under the large tree. As the view begins to track along with him, first person to cross him is a bare-bodied, manual worker.

Active interplay between castes and communities similar to this is common to Ray’s later village films like Aashani Sanket and Sadgati.

Then as the track gradually draws closer to him we begin to hear the ruckus between an old woman and a horde of boys his own age. Seeing them, Apu is amused almost like an adult.

Take a second look at the tracking shot. Not only is the boy contrasted in all kinds of ways with the villager he crosses—dress, age, profession—there is variety and contrast even in the greenery that he so incidentally passes. The large canopy of a tree, the palm single with its typical spread of leaves, a common aak bush (Calotropis) in the foreground, the banana plantation in the background, and of course the grass sticking out all along his route. It would seem that Ray built his nuanced expression through conflict and contrasts on as many planes as he could possibly incorporate in his frame.

But beside the frolicking boys, something else catches the young priest’s attention on the other side of the slope and he keeps turning to look back in that direction even as he descends another slope carefully holding the idol and the basket.

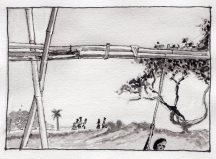

This one is a new visual set up where we see a bamboo footbridge in the background. Further narration is going to use all these elements in an amplified manner when the action returns here.

Apu stands watching the school the same as he stood watching the train a while earlier. The same indeed as he had stood variously amused, curious and mesmerised watching monkeys, Nand Babu trying to hide bottle of rum and the body-builder with Gadha on the bank of Ganga.

But before we move further, a question. What was Apu out for in the first place? Carrying a basket(?) in one hand and idol in the other, what was his purpose? Nothing is clear.

It’s almost an imposition with the sole purpose of bringing out the oddity of his profession when outdoors among boys his age, something that cried out to be ‘corrected’. His wanting to join them in school was therefore, not an act of rebellion as it could be in another character, but a ‘natural’ urge. That would be interpreting Ray’s stance here.

Night. The lantern, Apu lying face away and his shadow fanning out on the wall. Mother joins him on the bed with her needlework and does all the talking. Is he unwell? Somebody said something? There are nice people here…

Suddenly the boy wants to say something and rolls over into her lap. Whispers that he wants to go to school. Mother listens attentive, asks some basic clarifications and finally smiles approval.

Everything is over in just two shots. The concept makes it easy for the boy to perform. All he has to do is speak his lines one after another and roll back to look up at the mother while asking his last, “Don’t you have money, Ma?”

In a learner-filmmaker’s hands such a scene would usually end up having a heavy- handed approach. There can be no denying for example that the boy is sad to begin with and to most novices that would suggest to begin the scene with a close up. Having written which all they can do, then, is to go hammer and tongs after the kid to ‘act’ degrees of sadness… Naturally, a child can do no better than just make faces. Or worse, be a Bollywood child star.

[To be continued]

Sir

Thanks for another exciting article.

Regards

LikeLike

Glad you liked it Amit, thanks.

LikeLike