Fade to fade, this is again a single scene chapter and an account, as it happens, of the same evening as saw Sejo-bou’s campaign and Durga’s beating. This is also the only all-night chapter of the film and runs over 7 ½ minutes on the screen.

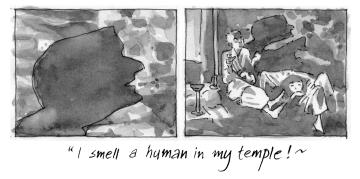

Fade in. Pishi holds a story telling session with the children. A one shot scene.

A simple concept—from abstract, pull back to the concrete; from comment, withdraw to the argument; from detail, get back to reveal the whole.

Technically, what is critical is the angle of seating Pishi in relation to the wall and the angle and position of the source light. (It’s in some ways like being able to neatly park a car without too much of back and forth.) Ultimately the shadow has to be flat enough to register on a smoked grey wall and oblique enough to retain the quality of a caricature. But the whole exercise has to start by first finalizing the old actress’s posture since that’s the one to be generating those shadow patterns that you are after. That she is narrating with her head raised is crucial for a well-defined, recognizable shadow with which the shot begins.

As noted earlier, creative manipulation of shadows has been introduced at the end of chapter 2. That was the second night sequence of the film, the first being the night of Apu’s birth in chapter 1, where no shadows have been used. Thus in a graded application—no shadow, part-shadow and all-shadow—the idiom has been gradually consolidated over the first three night sequences of the film. That done it becomes a part of the vocabulary of the film.

Notice the position of the children in relation to Pishi. It’s not one on each side of Pishi as can be one ready possibility, but Durga on Pishi’s lap and Apu on Durga’s. Apart from too geometrical a symmetry of one child on each lap with Pishi in the middle, the decision to keep Apu away from Pishi stems from a major mise-en-scene consideration for the whole film.

In the film’s reckoning, Durga has a special attachment with Pishi and this is borne out by a number of events, incidents, plots and sub-plots in the story. Ray uses all these in his adaptation, plus does something else too—nowhere in any one of his scenes does he allow much proximity between Pishi and the other child, Apu, thereby creating a feel of distance between them. It’s remarkable that nowhere in the entire film do we ever see Pishi and Apu actually touch each other! The idea is as witty as extending the other line in order to reduce the length of a given one. Working sub-consciously, not only does the device ensure a feeling of distance between the two characters but also provides its simultaneous justification. Altogether, seeing the film it strikes you as perfectly natural that of the two children, one happens to have a special attachment with Pishi.

Sometimes filmmakers create specific associations to further their worldview. Visiting FTII during late 80s, the Czech master Jiri Menzel took us by complete surprise when he revealed that he never presented any of his positive characters as smokers. Apparently he observes this in all his films. Likewise, speaking on censorship and violence during his famous India visit, Michelangelo Antonioni declared: The violence of the oppressor on the oppressed is wrong and should be censored.

The father’s arrival is entirely off-screen and is handled all in terms of reaction of others—of the disruption it causes to the story session, and of the coming to of Sarbojaya from her hurt of the morning.

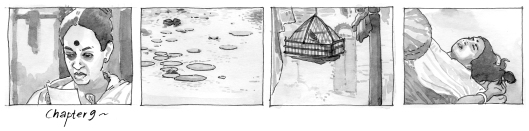

That this is the night of the same day that saw Sejo-bou’s charge and Durga’s beating is established solely by Sarbojaya’s silent posture. But for this unmistakable look of deep hurt, this could be just any other day. Even Apu asking Durga in confidence about the necklace before sleeping needn’t necessarily be the same evening. That Sarbojaya is allowing both children with Pishi is also a penance of sorts on her part for her violence against Durga in the day.

Durga brings a large fish that father has brought, which Sarbojaya listlessly asks to put down. The eager-to-please smile on Durga’s face is in sharp contrast to the sullen looks of the mother, and immediately sets them apart from each other in their response to the bitterness of the morning.

The first time we saw Sarbojaya cooking was at the end of chapter 1. That was a contented housewife with the family around and full of hope. This second time round it’s night and she is alone in her worry—a shade greyer but still not without hope. The third and the last time she is going to be sitting cooking like this—in exactly the same posture in fact—would be towards the end of the film when all is lost for her.

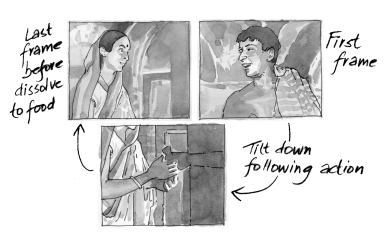

Handing over cooking to Durga, Sarbojaya comes over to a bubbling Harihar as he sits wiping hands and feet after wash.

Notice the common axis of this and the next shot in which Harihar rises to hand her the money. In both the plinth of the veranda has been used to progressively gain the low-angle look and feel of the scene, so crucial for Sarbojaya’s lit-from-below expressions at the end.

Notice, too, the staging of action and the camera movements, in other words the mise-en-scene. To begin with she comes to stand as he sits. Then in the next shot, he rises into the frame but soon the view tilts down as he takes out the money. It pans as the money changes hands and then tilts up to see Sarbojaya’s reaction of relief, sublimation. All this poetry-geometry is directed to mainly build-up and catch Sarbojaya’s emotion at having received the much needed but too-good-to-be-true money. The dissolve to the next shot—food—would otherwise not work.

That Harihar has received salary is not a total surprise—the large fish and the cheer on Durga’s face had already announced it to an extent. She needn’t any more bother Harihar with details of Sejo-bou’s campaign. And she doesn’t.

The dissolve from Sarbojaya’s face to food anticipates that celebrated long dissolve from the same face to the tranquil waters of the pond much later into the film when she receives a positive letter from Harihar.

Both situations are comparable—both provide relief and succour to Sarbojaya in moments of severe stress resulting from deprivation. In both cases Harihar is the deliverer, wish actual money as here and a promise of it in that later, more threatening situation.

The food. And Harihar eating it.

Notice that visually the food looks plentiful. That’s mainly on account of the heap of rice in the foreground. Even if you can’t see the fish, it’s there from the way he eats it.

Notice also the unmistakable correspondence between eating good food and the elaborate, indulgent and boastful monologue that Harihar goes through. While Sarbojaya keeps asking him cautious, deflating questions, he is on top of the world. This has been the basis of their relationship throughout the film.

To be sure there have been three major scenes between the husband and wife in the film so far, and in all three the course of conversation has gone on along identical lines.

The first was in the kitchen at the end of chapter 1 where Harihar had been trying to enthuse Sarbojaya to cook for a community feast. The second time was in chapter 2 just after Harihar had promised a wrapper to Pishi. He had just sat down next to Sarbojaya when she began to enquire about his salary stuck for thee months. And the third time is now, in the kitchen but at night, when Harihar is again somewhat pompous and upbeat.

The conversation over, children run across in the background.

Firstly, it’s an extremely well timed entry of the children in the composite shot—the conversation is just about over when they enter.

Second, it’s not without prior warning that the action has been suddenly staged in the depth of the shot. The earlier shot where Durga had brought the fish was from a similar viewpoint, and after she left a soft-focus figure of Harihar had been shown crossing the frame. That was introducing the visual idiom ahead.

Finally note that the two shots over which the children run to their bed are both from the same axis and the cut is timed on Sarbojaya’s reaction to the children in the first shot. The technical smoothness of the cut comes from having the children again enter the frame in the second shot. Trying to make a physical match cut would look too abrupt, as though a beat had been missed.

Incidentally, the present one has been Harihar’s second homecoming in the film; he had first been shown coming with Apu returning from school in chapter 2. Notice that the custom of washing feet in rural Bengal has been introduced partly in the first and the rest over this second arrival. While in the first the camera followed him right till he took off his footwear in the veranda, the second picks up the action from precisely that point and goes on to show him washing and wiping his feet before he gets up to Sarbojaya. The whole act is shown in detail at the end of the film when he returns after a long absence to learn of Durga’s death.

The custom is also reiterated at the end of chapter 5 when the unseen Raju welcomes Pishi in his house and asks for water offered her for washing feet.

The children in the bed.

Notice the sheer brevity of the scene. Even so it’s in two visual styles: one, running to bed and quickly settling down and two, asking the key question at some leisure.

Notice the richness of action the children have been given to perform in the first part. Durga opens the window while Apu blows off the flame. As a result, the view is left lit up by the moonlight. This same moonlight is going to be raining magic over the courtyard as Pishi sings her prayer at the end of the chapter.

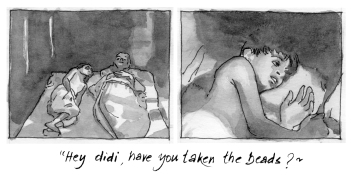

Notice next the changeover to the slower rhythm. Durga takes on the eyes-closed, sleeping posture as soon as she lies down. Apu too settles down and takes a turn towards her. The view dissolves closer to Apu, the stance being stealing closer curiously… Once there, it remains on him even for her replies. For one this avoids over-stressing and secondly it enhances the ambiguity of Durga’s replies. Incidentally, this is one of the very few lines that Apu speaks in the film.

Harihar to bed while Sarbojaya sits sewing.

The scene has just two lengthy shots. And they are in different rooms.

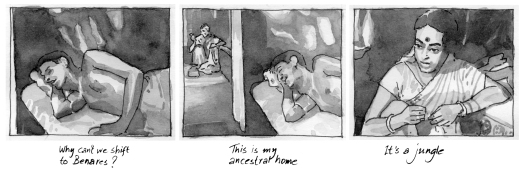

His stomach full Harihar is thinking of writing a new play while Sarbojaya sits talking from the next room. By the time she comes to speaking her heart, he is fallen asleep. From being in different rooms, they are in different worlds by the time the scene ends!

Even though the shot starts from a close view of Harihar in this room, the main source of light is the oil lamp by which Sarbojaya is sewing in the other room. This was the same lamp put off by the children just before going to sleep. Although never quite underlined, even the subsequent use of the lamp shows that the family uses only one lamp in both these rooms. Thus, once Harihar lies in the bed, he is getting none of the earlier highlights from the lamp and is lit solely by moonlight reflected off surfaces through a possible window—unlike the children he is too far from that window to get a direct patch. After her sewing is done, Sarbojaya will come and lie next to Harihar—that’s where she normally sleeps, as shown at the end of the film—but he’ll be fast asleep by then. The distance this scene underlines between them will only grow.

Mother sewing by the side of her sleeping children is a universally recognised magic-image. Another celebrated use of this image occurs at the end of Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monagatari when waiting for the husband, the ghost mother tucks in her little son for the night and sits mending a clothe by the lamp.

Notice that the trigger that turns Sarbojaya’s thoughts to Benares and has her asking Harihar to move there is the hearing of the nightly train. That’s when the view pans to include her in the frame and stays there throughout the long one-sided talk. At the end of the film, it’s the same train we’d see Harihar lying awake and hearing. And that’s enough to make up his mind. The conversation here brings to bear upon his decision to move to the city at that point without needing to ‘discuss’ the subject afresh.

The train is heard altogether four times in Pather Panchali and those are the only quiet nights in the film—at the end of chapter 2, here in chapter 4, in 7 when Sarbojaya decides to dispose off her brassware and at the end in chapter 10. All other night scenes are basically noisy on one or the other count—the jatra performance, Ranu’s marriage and the stormy night of Durga’s death—so that even if the train were passing at those times, it had no chance to be heard. The famous train scene of chapter 6 is during day time. Sounds travelling distances at night, this day train is never heard in the village.

Notice constructional similarities between the parents’ conversation now and the previous scene where Apu asks Durga about the necklace.

Once the children are settled in the bed, it’s a two-shot. Likewise, the Harihar Sarbojaya scene begins as a two-shot. Next the view dissolves to Apu alone and here too the view isolates Sarbojaya in an intimate study. Even the camera tracks in on her just as it had earlier tracked in for emphasis on Apu. In fact so firmly is this discipline observed that the view doesn’t pan even slightly to include the children sleeping beside her. An arm of Apu’s, completely still, is all that is seen in suggestion and that too gets eliminated with the track.

Now for some symmetries. Durga sleeps off while Apu is still awake. Next Harihar sleeps (as too the children) while Sarbojaya is alone and awake. Finally, at the end of the film, both Apu and Sarbojaya sleep (this one in the same static frame!) as Harihar is wide awake and thinking.

Notice even wider symmetries. The night Apu was born, Durga was asleep in another room. When Durga lies dying later in the film, Apu is sleeping right next to her. Sarbojaya suffers the agony in both instances, aided in one and alone in another.

There is a whole divide in Pather Panchali between the world of children and that of the grown-ups, and each side can be thought of as “sleeping” to the other. Indeed the two worlds converge at Durga’s death—they clearly don’t in Pishi’s death—and the greatest dramatic sparks fly in that part of the film resulting in Apu’s growth towards independence and adulthood.

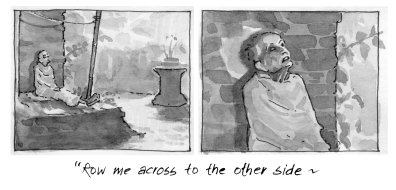

Finally, Pishi singing the boatman’s song.

Recall that the sequence had started with Pishi narrating to the children as the view opened up in a track back. It now closes in here in the opposite way: a somber song taking the place of a children’s story, and from a full shot showing the moonlit courtyard, the view converges to the old woman, alone. Earlier the head was raised perhaps more for the facility of creating a good shadow on the wall, but here it is raised for no such “earthly” purpose—it’s raised heavenwards, directly where she is addressing her appeal. The body posture remains identical between the two situations. In fact we saw the same body posture earlier on when she was at Apu’s cradle and singing.

Notice, nonetheless, that all these formal, symmetrical beauties would collapse in the absence of a very involved and authentic singing by Pishi. Given the old rustic, of course, the playback technique would be out, but even otherwise a folk melody such as this will have to be sung by the actress in her own raw voice and best shot in sync. (This is shot in a studio set, by the way.)

Ray had occasion later on to have similar singing situations in quite a few films and mostly used the actors’ voices and shot in sync. The old toothless villager in Postmaster is certainly singing himself and so is the Rajasthani beggar family in Sonar Killa. The beggar in Devi is an actor, and the singer therefore a studio-recorded professional. The local boy in Kanchanjangha is an exception on all possible counts where a mix of techniques had to be virtually pushed and the result shows.

As a film on abject poverty, notice that there is a lot of eating in Pather Panchali. It’s like a film on prison having a lot of emphasis on doors. And that eating has been spread out through the first half or so of the film. As Ray treats it, each character has been shown taking one major meal. Mostly it is one person eats while others look on, serve, or otherwise help.

Pishi eats in chapter 1; in 2, Apu is briefly fed for school but is hungry on return; his main eating is at the beginning of chapter 3 where mother feeds him while he aims an arrow at the dog. Harihar eats here in chapter 4 this sumptuous fish and rice meal at night with Sarbojaya attending; Durga eats in the next chapter along with Ranu (in the jungle), and, at the end of the chain in chapter 6, it’s Sarbojaya’s turn—the annapoorna image, if you like (eating last after everybody in the family has eaten)—when Pishi comes asking shelter, and settles for water.

Again, notice that Sarbojaya is not the first one to be sewing in the film. The business of mending clothes has been introduced from chapter 2, with Pishi trying to thread the needle but never quite getting beyond it. Here in chapter 4 the same act is as though being advanced by Sarbojaya.

Notice further that with both these women, mending clothes has been associated with loneliness. Pishi’s song, before we see her singing at the end, is heard off screen much earlier over Sarbojaya-Harihar conversation and continues subsequently over Sarbojaya’s isolation. Thus, both women in a way can be seen as serving to be each other’s past and future simultaneously. Sarbojaya is what Pishi’s state perhaps was once upon a time and Pishi represents what Sarbojaya could be heading towards. In fact Sarbojaya dies ultimately in Aparajito as a very lonely woman.

And likewise, indeed, for Durga. Referring to her own past in her poignant monologue, Sarbojaya says she had a lot of dreams once and a great many things that she wanted to do. And what do we see Durga doing in the immediate next chapter 5? Living those very dreams and ambitions out in the real, looking forward to the bliss of a marriage which we know—and she has a premonition too—she is never going to have. Isn’t Durga, then, a common past of both Pishi as well as her mother?

But finally, a masterstroke of construction, which is not immediately apparent about the sequence at hand.

In spite of a certain rambling quality of the narrative, the happenings of the chapter are firmly held together on a rigid formal matrix—the whole sequence is built up of a series of narrations in one or the other form. Pishi obviously in narrating a story to the children to begin with, but what Harihar does afterwards while eating is also tell a story—about somebody having approached him the same day for conducting a religious ceremony. Coming from a writer, it’s rather a skillful narration which arouses and plays with the listener’s curiosity, in this case Sarbojaya. Later, while retiring to bed Harihar mentions a play he is thinking of writing, which is narration itself. When Sarbojaya similarly recalls their initial years of separation without letters, it’s after all nothing but a chapter from their biography and when she is finally ready to bare her very soul, the listener is no longer interested—he’s gone to sleep. And when at the end Pishi sings with such abandon and devotion, does it matter if somebody listens or not? She sings to herself and to her lord, and is at peace.

In my experience—and to borrow an expression from carpet weaving—Ray’s cinema has the maximum density of knots per square inch. 10 years down this was the man to go ahead and make a film like Charulata where poetry romances with prose and blends, stitch for stitch, in an act of masterly love-making.

[To be continued]

An absorbing read. I consider it very technical to teach and generate… Hats off to you!! Looking forward to read the book 😊

LikeLike

Thanks Kusumji.

LikeLike