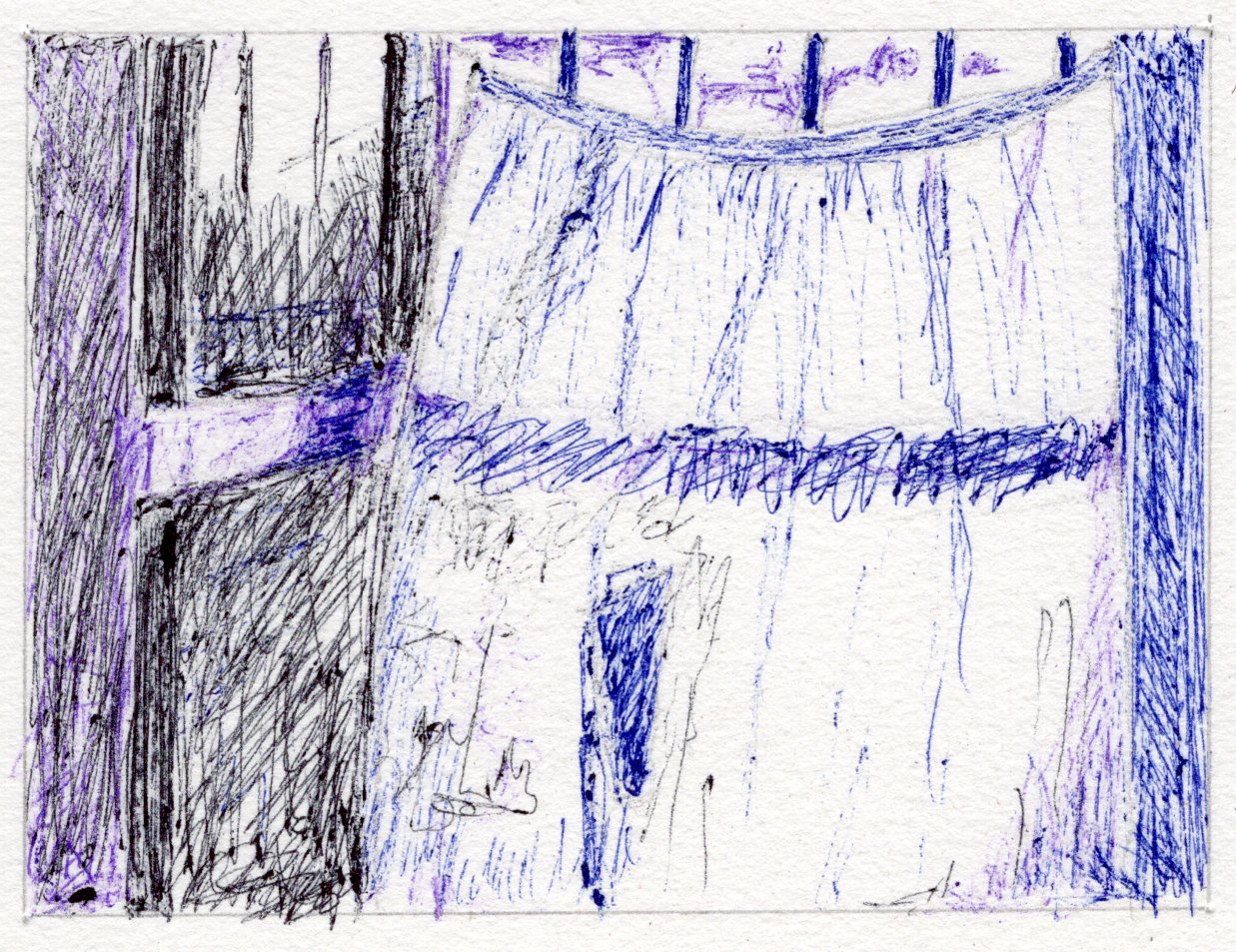

Fade in on a torn and billowing window curtain, dripping wet with rain. If already you do not know whose room this might be, the view tracks to include him sleeping on the bed, Apu’s. A hole in the middle of a cloth carries from Pather Panchali.

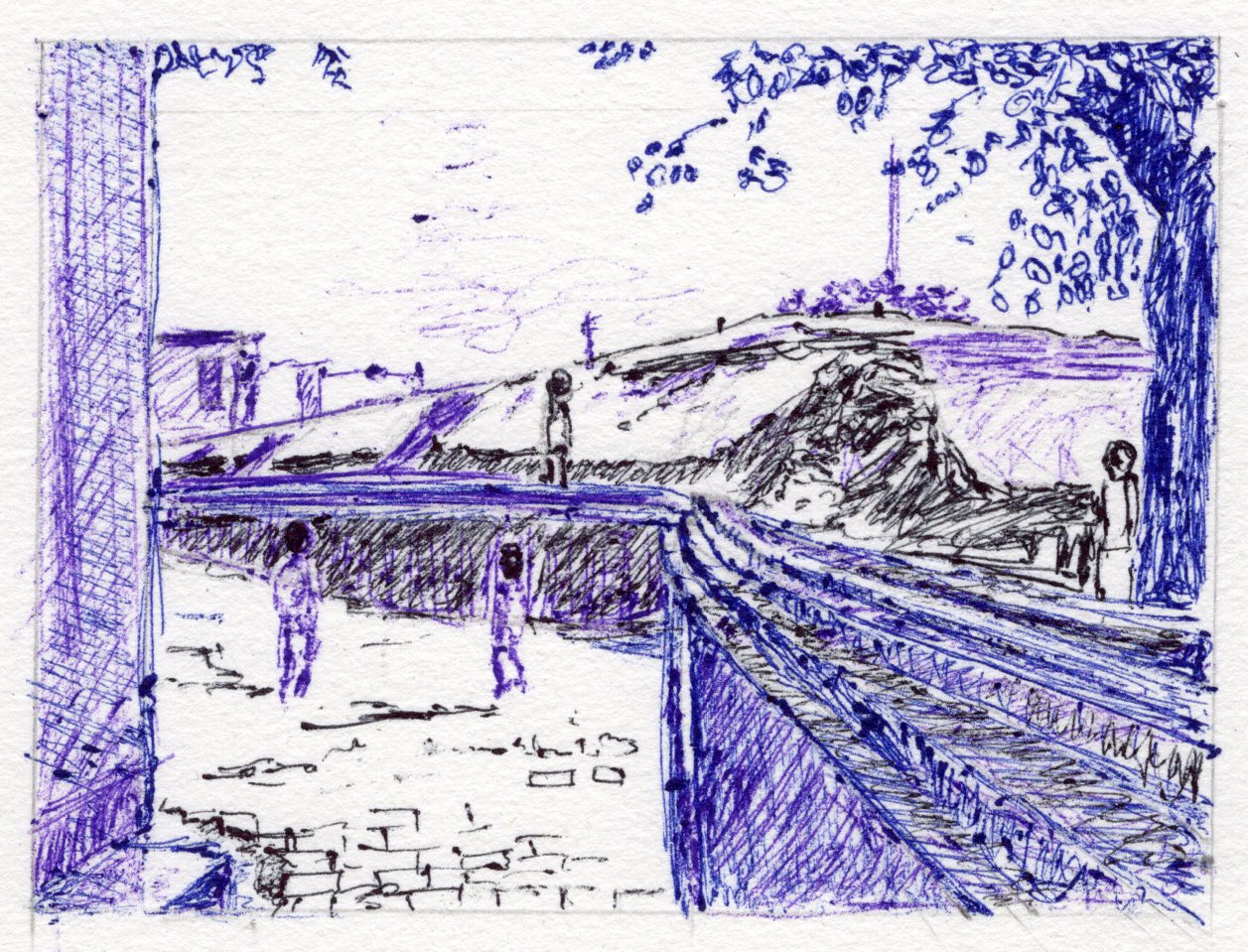

The place is by a railway yard because a long whistle from a shunting engine wakes him up. He grabs at the alarm clock and jumps; he’s late. Coming round the bed he discovers another disaster. The ink pot on his bed has toppled and…

The bulb overhead is on as he goes layer by layer and retrieves a folded shirt that he had left under there to ‘iron’.

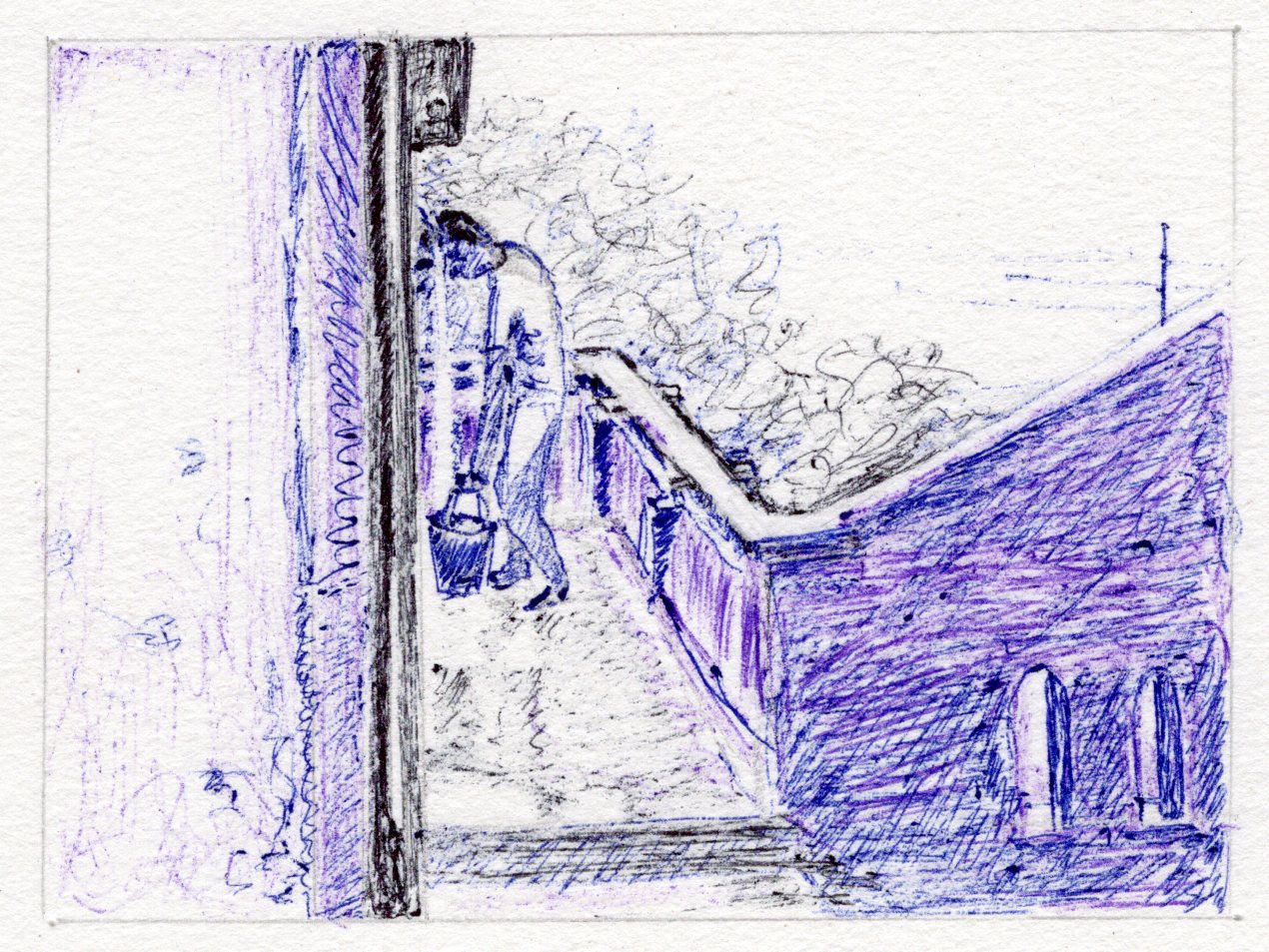

Now for damage control, the wash! He comes out…

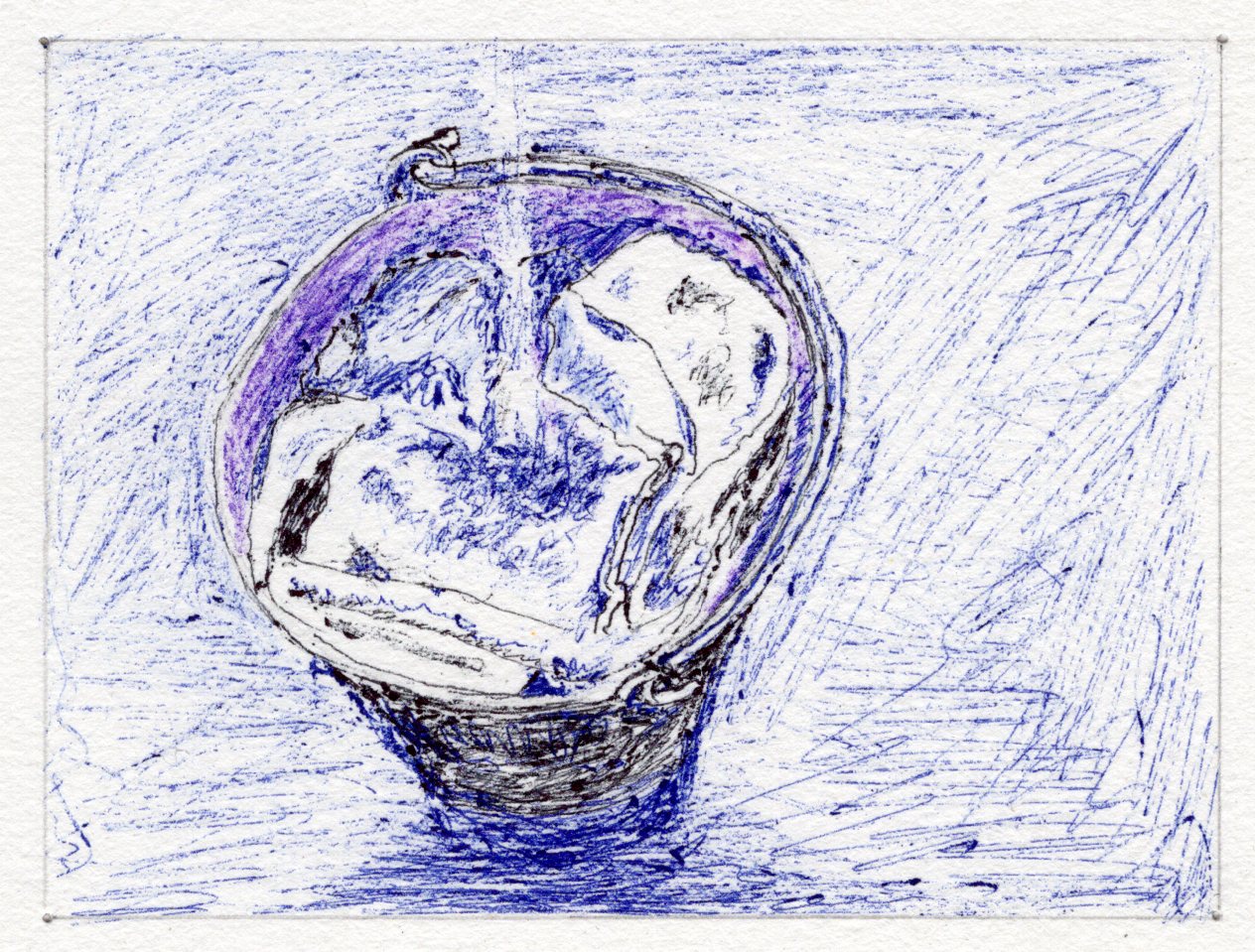

It’s pouring as he goes and dumps the washing in a bucket. For a large ink patch on the back, his own vest belongs there too but… The water? He goes past a pouring stream from the corrugated roof to check the position downstairs…

But they are short themselves, so he has to improvise. There he sees, another rainwater stream pouring…

…which he decides to put to use.

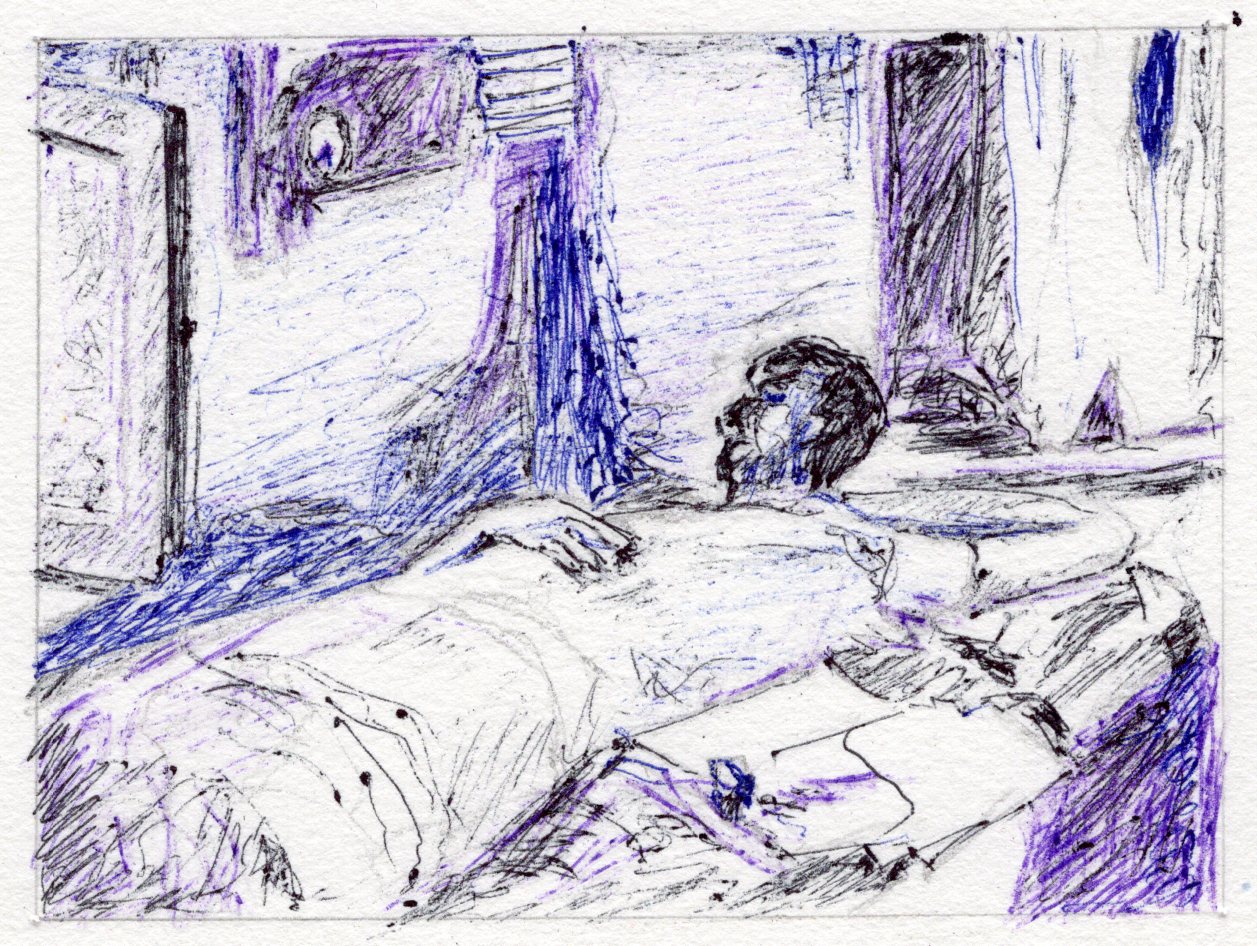

Railway whistles, rain, more whistles. Happy, Apu stands bathing in the downpour. We needn’t worry about his vest now, it’ll get washed by itself.

That’s introducing Apu, the hero of this film, indeed of the trilogy, as a young man.

Without our realising, this rain-drenched opening should unburden Ray from the task of introducing Apu’s house. We now know that he lives near a railway yard, in a room plus terrace on the third floor and shares amenities with neighbours down below. The rest of his time in this house is going to be built around these elements.

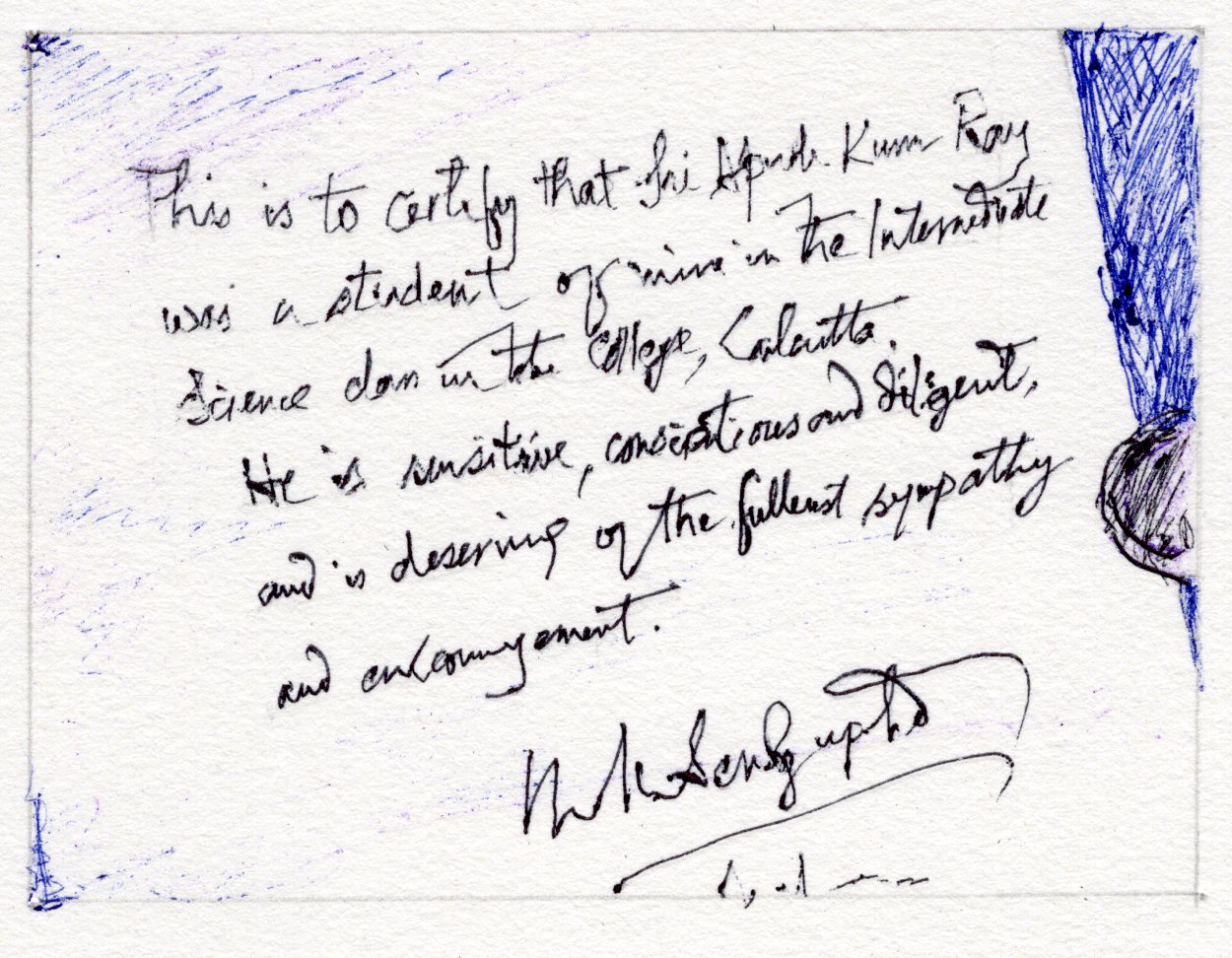

We also get introduced to Apu as a character. Apart from the obvious—he doesn’t seem much different from how he has been summed up by his professor—he has a way of adjusting to what life has to offer. A lot seems to be happening to him, which he is not even aware of. The ink patch on his back, for example, which gets sorted out by itself. Does the idea enlarge for him in some way by the end of the film? Indeed so, if we know the film.

That’s also, thus, launch of a character fit to be tested through surprises small and big.

What does he do for a living? Well, he starves while he looks for a job, as we would soon discover. But before that he has a visitor…

Notice the landlord’s entry. He could be a parody of a hawk! Enter Shylock, in a manner of speaking.

It’s an old practice among the best in the trade to conceive and model their characters after animals. For Rashomon, Kurosawa is known to have shown Mifune a cheetah; Eisenstein played his famous highly stylised Ivan as a mountain eagle.

Apu is shaving at the time of the visit. Shaving is important because later in the film he would have a beard. But equally when you are a pauper, shaving looks like indulgence. And to a landlord with your rent overdue, positively an affront.

><

Landlord’s lines are worth a repeat.

Apu: (Hearing a cough outside) Who’s there?

Landlord enters.

Landlord: Namaskar.

Already in his voice you can see a trailer of what his tone is going to be like, ironic.

Apu: Namaskar. Please sit down.

Landlord: Will it be fruitful, sitting down, Apurva Babu?

Apu: At least you would be rested! You climbed so many steps.

Landlord laughs as he sits down on a chair.

Landlord: I’ve not come here to take rest. What I have come for is what you know, as well as I do. So I ask you a straight question and you better give a straight answer. Without diversions.

Apu: Well, ask?

Landlord: What’s the date today?

Apu: 10th.

Landlord: How many months’ rent is due?

Apu: 3.

Landlord: 3, yes. 3 sevens is 21. So I want to ask you Babu, will I get it now if I wait? Or will I have to come back in the evening?

Apu: Oh god, you asked me three questions instead of one. That wasn’t settled!

Landlord: (After a pause) There was a lot else that wasn’t settled Apurva Babu! Was it ever settled that you’d treat this room as a dharamshala? Was it settled that you are consuming electricity during daytime? Tell me, you are educated, you have hanged pictures of great men on the wall but why are you so reluctant to pay my rent?

Apu: That is the sign of great men, don’t you know?

Landlord: (Getting up) I can’t match you in twisting words Apurva Babu. And it’s not proper for us elders to speak our mind to youngsters like you, so let’s leave it at that! I am coming in the evening. Keep the money ready. Otherwise I’ll have to find another tenant.

Apu: Straight talk.

But in response, the landlord switches off the light and leaves.

><

What Apu has received at the end of the landlord’s visit is not an ultimatum, only the latest of threats to vacate if he can’t pay up by the evening. Rs 21 at 7 a month.

Apu has a childish streak in him when he switches on two lights against the landlord’s one switched off as he leaves. Aparna, his wife to be, observes this in confirmation. And plays almost a mother to him.

Notice the set—for Apu’s room is a set—and its lighting. Against the normal practice of raising the heavy studio light to its highest and placing it outside the window in those days, the window here has been lit from the farthest point available in the studio to replicate the sun. That’s how the bars’ shadows appears neither converging, nor thicker than the original.

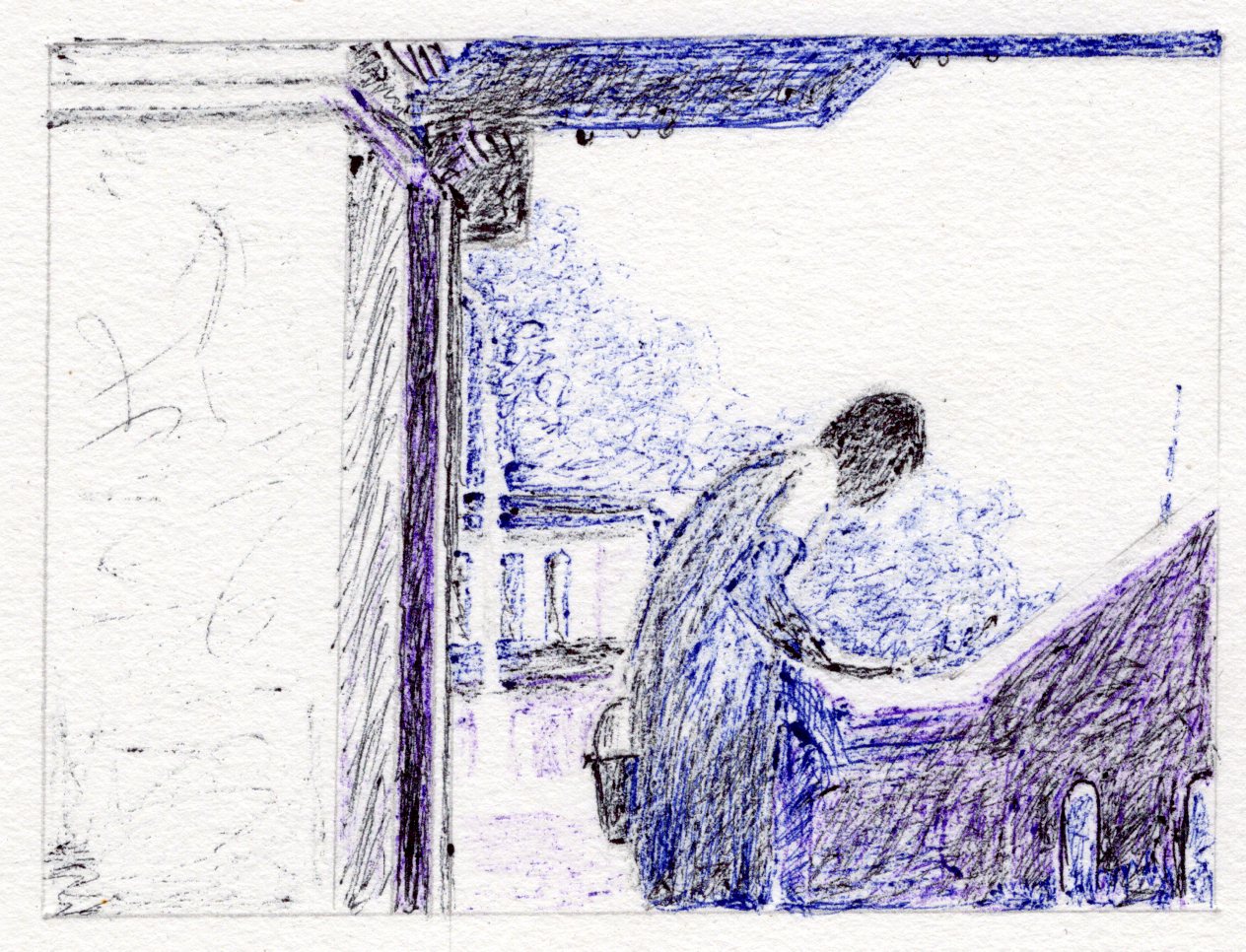

Leaving for the day, Apu takes a couple of library books to return. Before slipping them in the shoulder bag, he carefully saves a bookmark, a leaf.

This leaf would stick in memory. Primarily as a visual idiom of intimate, poetic and private moment—mainly for its sharp, piercing quality—and secondly the kind of forest—tapering, spire-like trees—that Apu is going to land up in. This image here seeds those associations for the future without which they will not work as well as they do. A peepal leaf instead, for example, would not work.

Notice, in particular, the multiple-layers, soft-focus of a telephoto image around its subject, the leaf.

Incidentally, both the books he handles are English books, the one with the marker titled Outline of History. These next to his old globe from Aparajito point to a continuation of interest in the wider world.

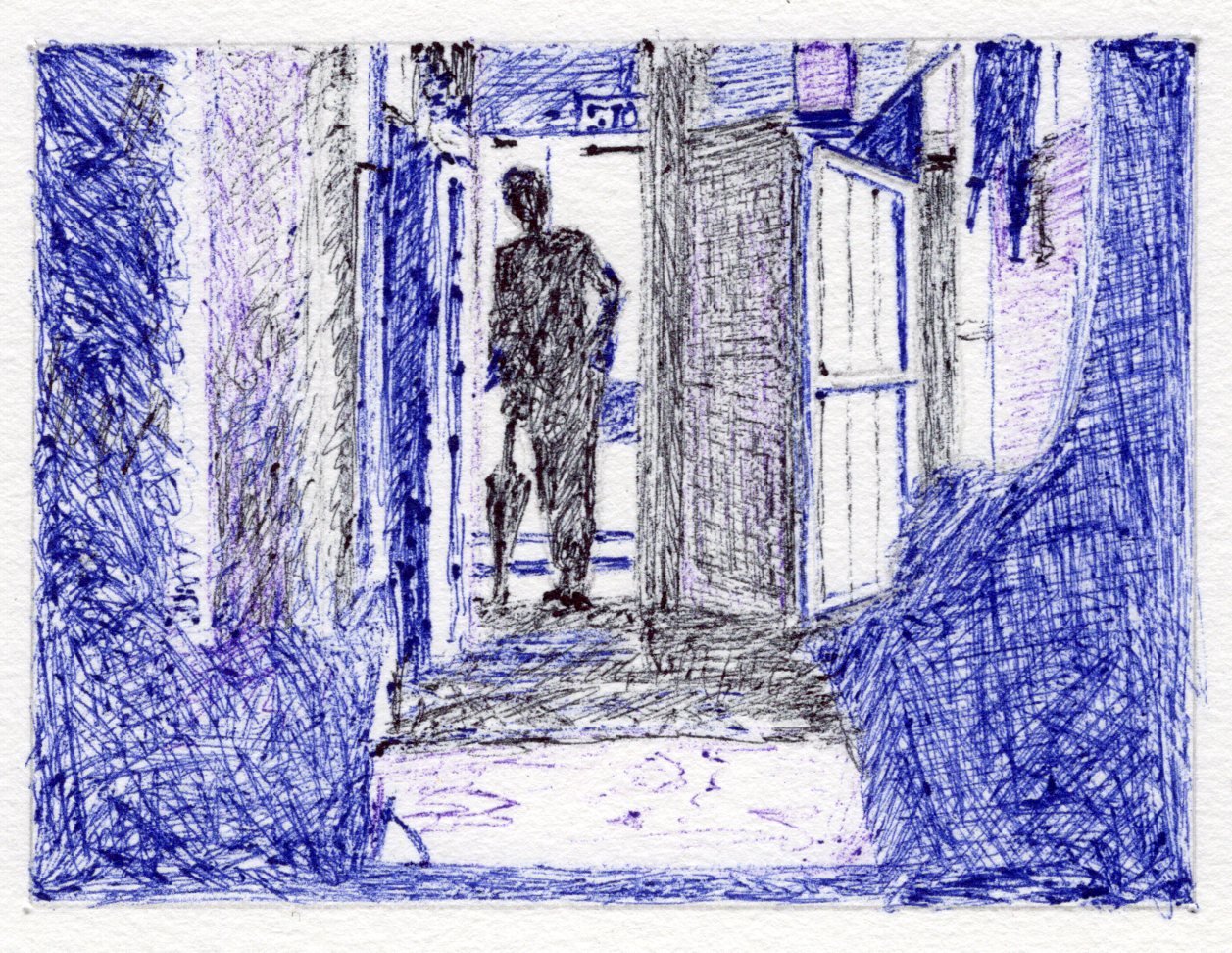

Descending the staircase Apu passes by a woman on the landing who abruptly covers her head to him.

But a more detailed interaction awaits him with another neighbour, another Roy on the ground floor.

Notice in the staircase shot the woman’s reaction. She is wringing, loud and clear, a washing. Secondly, to the left of frame, there is a large length of sari hanging on the line. While both may be aftermath of rain, both activities have been skipped for Apu’s own bucket of washing. So, in a sense, the wringing and spreading of Apu’s washing gets accounted for here. Plus, of course, the fact that there is nothing like a sari to break the visual angularity of concrete. Indeed, the rising smoke, too, serves the same function.

But there are more women going about their chores as Apu descends.

The fact that there are no men—or boys—around provides, most subtly, the impress of times. Women in general are homebound. And to present their range, there is even a girl in plaits he crosses carrying a bucket of water upstairs and another further down, a young veiled housewife, complete with her bunch of keys weighing over the shoulder. That young girl in plaits should be in school.

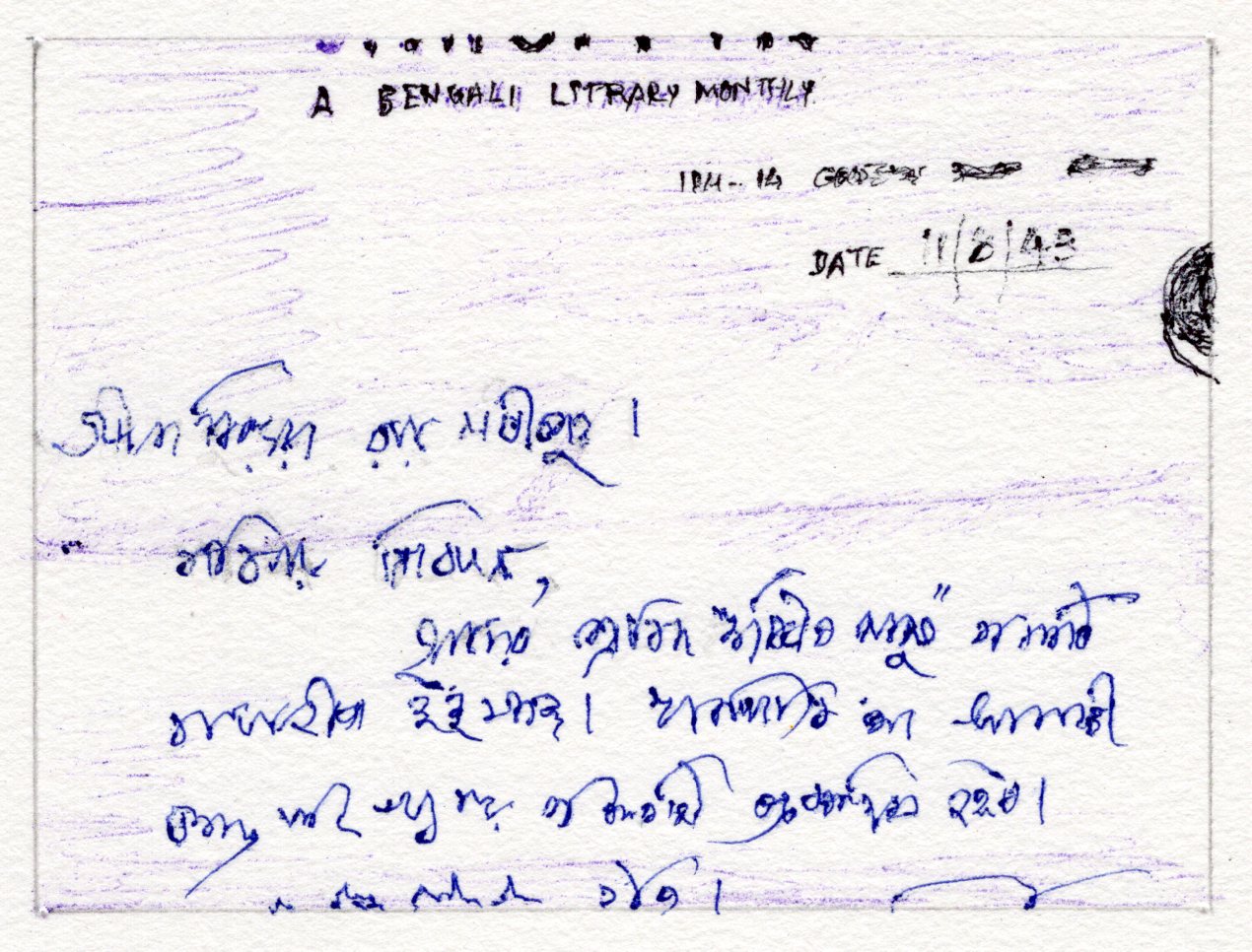

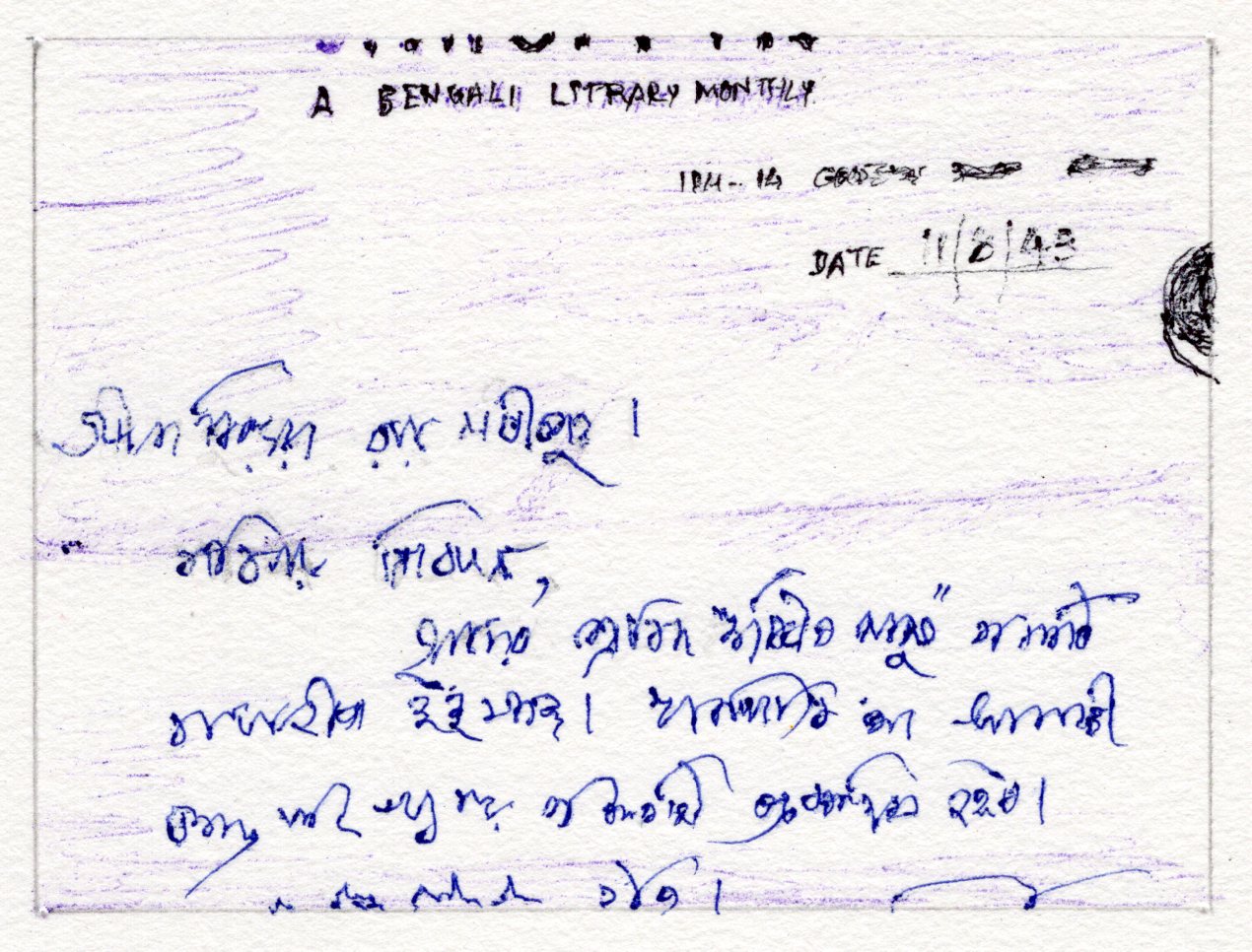

The nosey old bachelor calls him to hand him his mistakenly delivered letter but salivates to get some day to read one from his girl friends. The letter at hand, however, carries a more welcome news for Apu. A magazine has accepted one of his stories to publish.

Interestingly both responses from the neighbours, the woman at the landing as well as Mr Roy, have sexual undertones. These soften the pitch for a girl who at the end of the day waits for Apu in her window and eventually nudges the narration towards Apu’s marriage.

Notice the letter, especially in the context of the first one that the film began with.

Both letters have Apu’s thumb in suggestion, both have been kept on the screen for their reading time and both are seen hand-held and shaking within a camera frame that has been locked for its pan and tilt. Both letters are variously upbeat in their content for Apu and formally, both lend credence to each other as style. Subsequent letters in the film would be treated differently.

Shots like these are difficult to take particularly because of critical focus of the macro lens that’s needed to capture them so close. Once a way has been found to rest the holding hand at the required distance from the lens, they would usually be taken together, one after the other. The letter from the publisher in addition also opens out in the shot but not fully flat so that only the content lines are sharp in focus while the date and publisher’s logo are in soft focus and partly out of frame. This would be altogether a more demanding exercise.

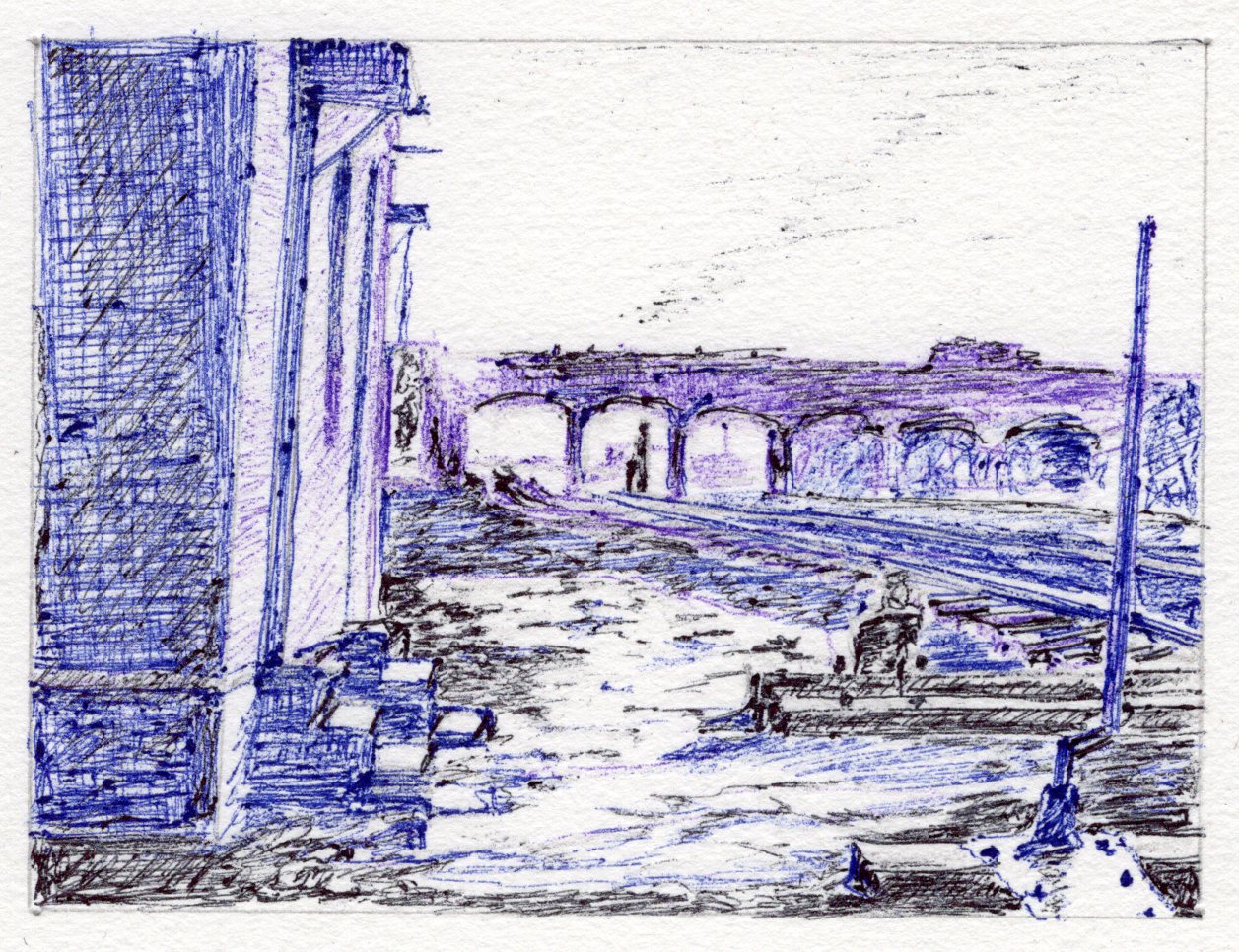

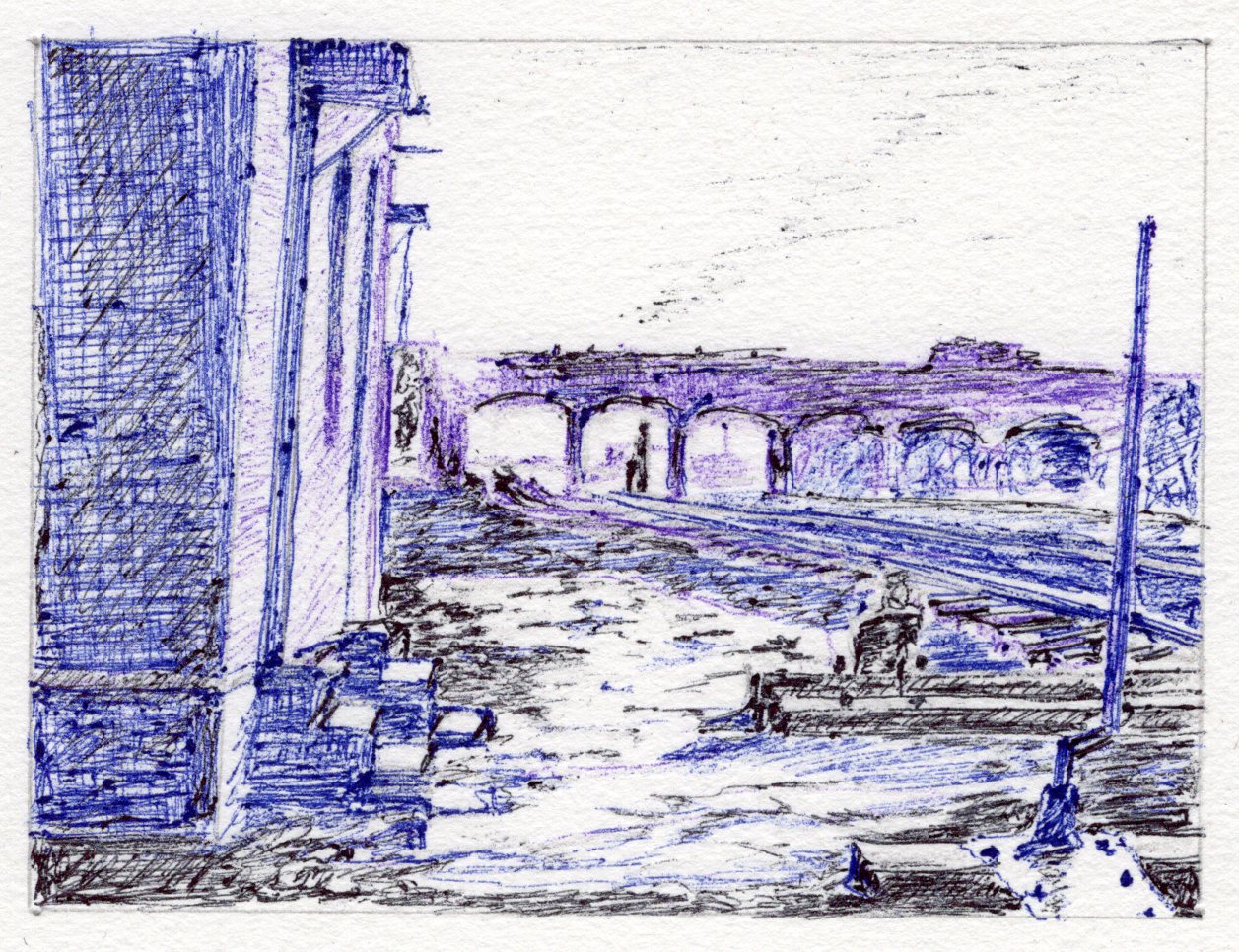

Remarkably, the shots of Apu having finished reading the two letters has two common features: One that they are both low angle and two that both have arches immediately behind Apu.

These would be designing touches to suggest, if not commonality of the two situations, certainly a kind of poetic rhyming. Both situations, very subtly, remind one of the other.

Notice that Mr Roy’s being a corner room, Apu enters from one door and exits directly into the street from the other.

A visual wit, one among a whole variety of them that Ray is fond of using. In addition, this device here re-establishes the building’s proximity with the rail lines, which we can see behind Apu through a broken boundary wall.

><

Apu’s job hunt begins with receiving a hit in street cricket. Even before the teacher has joined, the pupils have scored, you might say.

He has come here for a teaching job and these might be his pupils if he gets it. On the wall is a board that says the school started in 1902. Inside, the bald irate headmaster is busy playing a game of dice with his cronies. He is positively interrupted. The interview takes place standing, from across the empty classroom.

Apu says he is an Intermediate pass. He is dismissed for being overqualified. When he mutters protest, he is asked if he would accept a salary of Rs 10. Knowing the room rent alone, we know his answer.

Next he is in front of a ‘medicine factory’ owner. Says he is a Matriculate. His innocence draws a smile from the kindly man, who asks him to go inside and see the ‘labelling’ work that he has come for.

It’s a menial job, 10 bodies to a room, sticking labels on heaps of tiny bottles. The thought is an assault on his bhadralok culture. A worker’s gaze sends him squirming and Apu has to look away. We needn’t know the salary.

Next to the door that Apu stands looking in are a bunch of shining glass lengths, which he doesn’t even notice. These must be pipes, which are first cut into little bottles in another room and then brought here for labelling. Ray was aggressive on detailing which needn’t be of immediate relevance to the narration but would lend value if noticed.

It being a rainy day, the whole development has a generous sprinkling of umbrellas. The landlord’s to begin with, the one that Apu carries himself as he leaves home, medicine factory owner’s hanging on the wall in his office and a number of them belonging to the workers hanging in the passage.

Compare and contrast the interviews for their mise-en-scene. One opens with children that he’ll be required to deal with if selected, the other ends with workers that he’ll have to sit beside if he gets the job. The first one he can’t accept because of low salary, the second he opts himself out of since, salary notwithstanding, he can’t see himself doing that kind of menial job. In the first all parties involved are playing instead of being on the job—those to be taught, cricket and those teaching, a game of dice. In the second everybody is at work, he is offered a seat, treated with respect and asked to see the job he’ll be required to do.

The implication is that between these two ‘extreme jobs’, Apu may have appeared for many others which fell on this or that side and he was unable to take.

><

Apu stands taking free air in the entrance of a tram.

He buys his ride and tries to draw comfort from the letter from the magazine. We never saw him eating a meal but the letter rejuvenates him.

Notice details of the area the tram is passing through. Visible in the street behind him is first another tram crossing and after the view clears, two cars parked by the curb, both of pre-Ambassador vintage. You wouldn’t notice them in the running film but it’s through such casual slip-ins that Ray breathes that authentic period look of his films. You didn’t notice and yet they didn’t fail to make an impact on your sub-conscious.

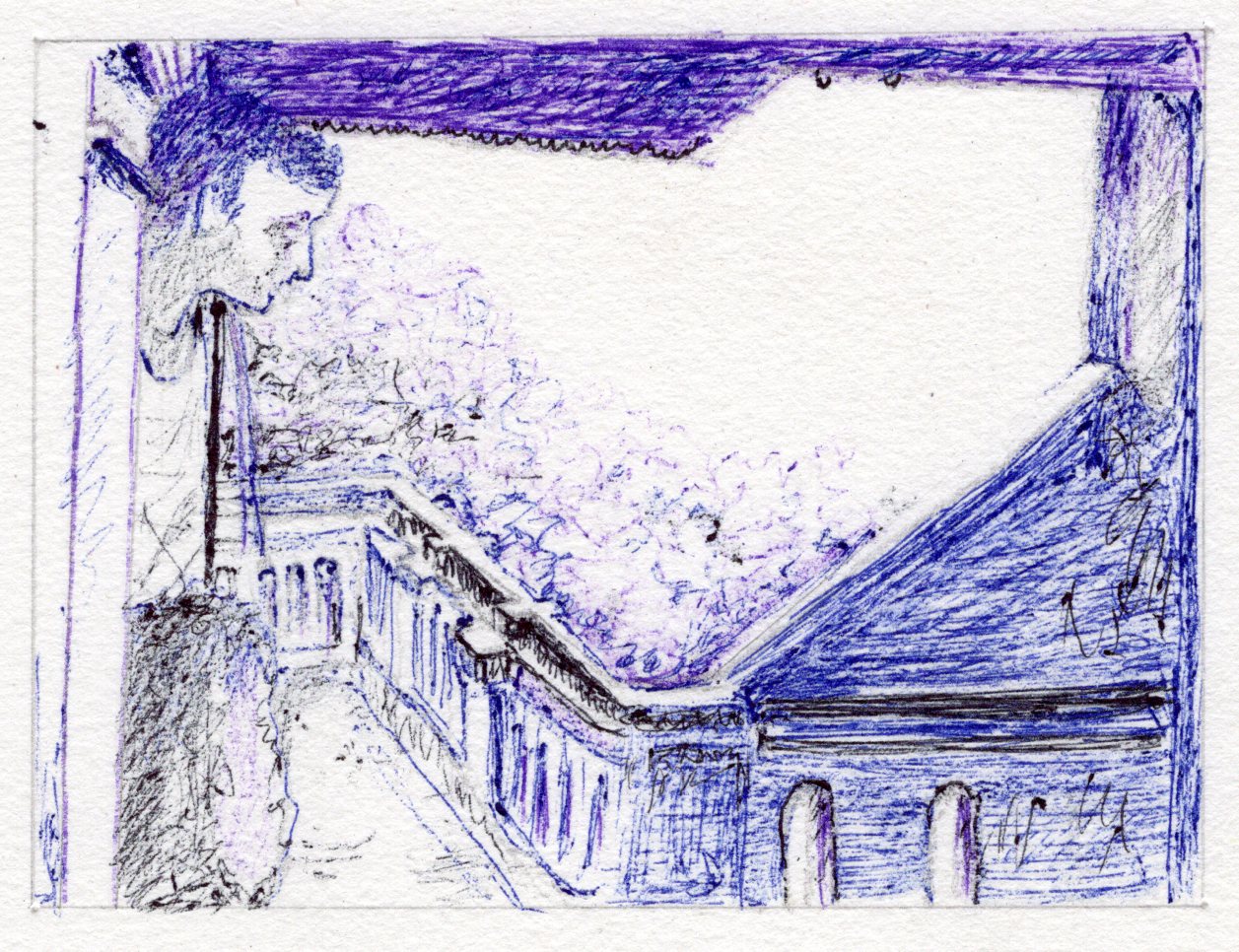

There is a bounce in his gait as we see him coming along a network of railway lines.

A flock of pigs crosses the tracks even as stray individuals do the same farther away.

He jumps over a broken boundary wall and is home.

Notice that both shots showing his approach to the house are back lit, thereby reinforcing wet reflections of a rainy day. All along, the umbrellas and now, this.

Notice that rather than repeat the staircase, Apu’s homecoming is picked up from inside his room which he unlocks and enters.

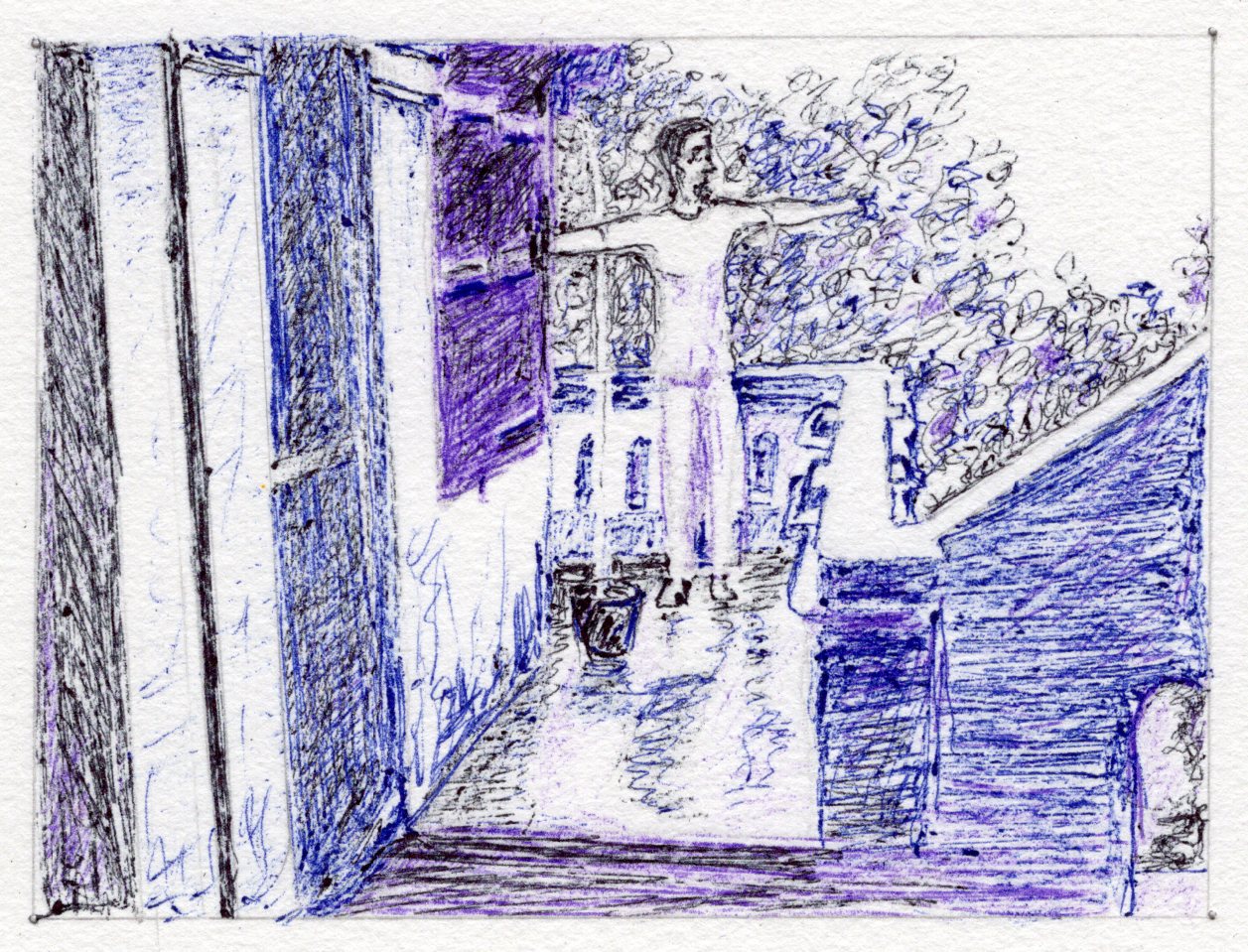

From across the street, a girl waits for Apu. As soon as he settles down after changing, she presents herself in the window. Apu gently closes the window and goes for his flute…

Consider, as example of richness of Ray’s imagery, the girl in the window. It may not be immediately apparent but there’s a lot qualifying this image before, during and after the shot.

As Apu enters his room, he doesn’t switch on his ‘famous’ light. The window in front is a good enough source (both for him and Subroto Mitra) and we see him variously unload himself. Nothing has gone right for him except for that letter from the publisher. Rather than earn anything, he has had to spent on the tram fare. We never saw him eat, not even drink a glass of water. His room—it’s rent overdue—offers him the comfort and freedom to toss his things about as he likes. Everything is thrown from a distance except the shirt, which he probably would use the next day.

That’s when the girl in the window happens. We have been aware of this window all along but are seeing through it for the first time. One glance and we see what has been missing in his life, a woman. And she appears just when he might need her most.

The shot is a frame within a frame. Both windows are barred and there is a street between them. The girl is backlit with a naked light bulb behind her. That was the exact light hitting Apu as he entered his room. And that’s the bulb now burning into her silhouette just as a couple of shots before, the setting sun was burning into the bridge as Apu returned home negotiating those tracks. Indeed just as at the end of the scene, a strong light from a shunting engine is going to be hitting the same bridge as Apu and friend Pulu return from a happy evening together.

We wouldn’t recognise the girl if we met her on the street—perhaps Apu wouldn’t too—but she seem a good-looker alright. And no doubt she has her pride. Just as Apu quietly closes the lower half of the window, she moves away before he shuts the upper half. A woman of some substance, we tell ourselves.

That she is behind social bars can’t be denied. As noted before when Apu was descending the staircase, women were homebound and even girls tended not to be sent to school in those days. Through all his checkered education over PP and Aparajito, Apu himself never studied in a co-ed.

Finally notice that an amorous encounter that he denies himself here is eventually more than made up with his wife. Their ride back home from a film where wife Aparna lights his cigarette is portrayed as though with a courtesan. That was the last intimate scene of the couple—the peak of marital bliss for Apu—before she is seen off at the railway station and indeed for good.

So, Apu denies himself a chance of an affair and goes for his Art. His writing with which the film began—the toppled ink pot—and the flute introduced here for the first time.

Notice the shot of Apu playing the flute.

Using only pan and tilts thus far in the film, for the first time the camera tracks back to reveal Apu playing this beautiful piece at the end of a tough day in the middle of his pauper circumstances. A summing up of sorts, this track is good to extract a “Wah!” response from even the most artistically illiterate among us.

A number of thoughts are triggered. Artists, it would seem, need that hunger and deprivation to produce art. Women inspire us to do great things and then keep distracting us from achieving them, as a famous wit said. Apu’s writing gets all messed up through marriage. It rocks his boat so violently as to send him suicidal when his wife dies and it takes a herculean effort to resume with some hope.

Notice the composition of the flute shot. Up there, un-emphasised in any way, is the globe and balancing it is another round object in another corner of the frame, the globular, earthen water pot, surahi. There is a strange white clutter under the bed, which lights up that otherwise dark space but is completely unrecognisable for what it might be. It may well have been Subroto’s idea to ‘put something there’ and between Bansi and Ray they have provided, rather than an identifiable object, this. In the event, it becomes something of a visual scribble. Who said things exist for us to identify and comprehend? There is a lot that we see around us which we know nothing about but it is there, it exists. There are corners aplenty around behind which we can’t see but those corners hold out the promise of a discovery and are interesting for that reason. That’s life and that indeed is Ray’s cinema. Art doesn’t offer you things and ideas on a platter but challenges you to engage with what is presented.

><

As observed in another context before, notice the proximity of sun setting critically behind the bridge as Apu comes up along the railway lines and the equally critical light behind the girl in the window.

Likewise, notice the similarity—and criticality of angle of viewing of the walls involved—of the boundary wall in front of his house and the one when he enjoyed a bath in the rain as his bucket took the water pouring from the roof.

Again, nothing but a scheme of twos in terms of design. And each lending strength to the other.

><

This completes the second part of Apu’s introduction. A day in his life you might say.

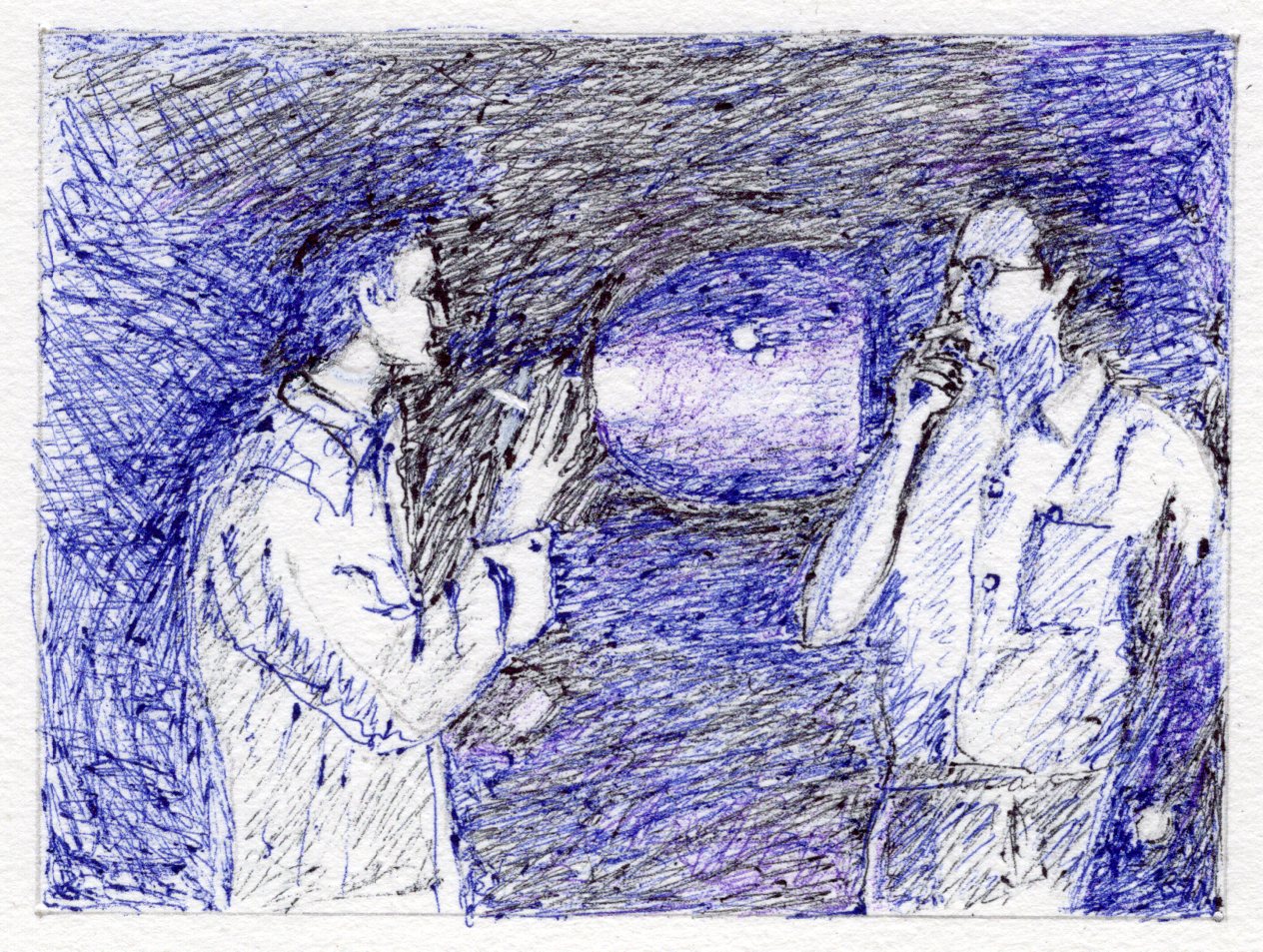

Except for a surprise turn—there is somebody on the stairs. Just when you dreaded it was the landlord keeping his word from the morning, it’s Pulu, a friend.

A perfect rendition of the expression, “a pleasant surprise”.

A scene that was almost ready for a fade out gets a new lease of life. And a new lively pace. In one uncut shot, with the camera doing nothing more than generally cover the action, the two friends renew contact. Next, they are eating together in a restaurant. Next, wandering the streets late into night, poking fun at an unseen policeman, exchanging banter, discussing plans for the future. And before you realise, they are both in the countryside where Apu accidentally finds love…

Come a friend and the whole course of Apu’s life changes. This is the subtext of this sudden change of style of the film. Considering his intervention later again in the film, Pulu would seem to be an agent of fate to bring Apu’s life unstuck.

Notice the switch to the restaurant. They had gone there to take tea but by the time we find them at the table, they are in the middle of a meal. The track with the waiter helps to bridge this gap. Rather, they finish the meal with a cup of tea as the scene ends.

In contrast to Apu’s life so far, restaurant’s is a world where eating is celebration.

On the same momentum, when we see them declaiming poems on the bridge, it’s implied that they have already seen the movie for which Pulu came saying he had the tickets. Later on the narration would take us to an actual film in a theatre, with Apu and his wife. Likewise, we have just seen Apu in a tram taking out a letter, the one from the magazine, to read; next time round there would be a detailed scene around reading another letter, this one from his wife. The beauty of such applications with Ray is that you hardly ever notice them as technique.

One of the pictures on the wall in the restaurant—out of focus like everything else there—is that of the writer Saratchandra Chatterjee. That’s the popular writer Apu’s professor mentioned at the beginning. The restaurant is probably Apu’s regular haunt. As it may have been that of the popular writer, who knows?

Incidentally, Ray never adapted any of Saratchandra’s novels.

Also, as pictures go, there was another in the office of the label pasting job, Ram Krishan Paramhans, a 19th century Hindu mystic from Bengal. Things tend to happen in twos in Satyajit Ray.

Notice touches of flourish in the restaurant scene. The ‘smart-Alec’ opening track where two plates collected by the busy-body waiter happen to be for another table; the cracking response (on the sound track, this) of another waiter to Pulu’s call for tea; Pulu’s overall ease of conduct in a restaurant.

Notice the casting of Pulu. Plump of built, wearing glasses, and unlike Apu, more a man of half-sleeve shirt and trousers rather than dhoti. The two together can never be mistaken for each other in a long shot. As character, Pulu’s manner is that of attack. He enters Apu’s room giving him a blast about how many places he went looking for him before coming there. In the next scene, he describes the beauty of countryside in so many ways before extracting a yes from Apu for the visit. And you can’t fail to notice that between the two friends, he eats with a western fork and Apu traditionally with fingers. Later in the film he goes abroad and returns once again to restart Apu’s stuck life.

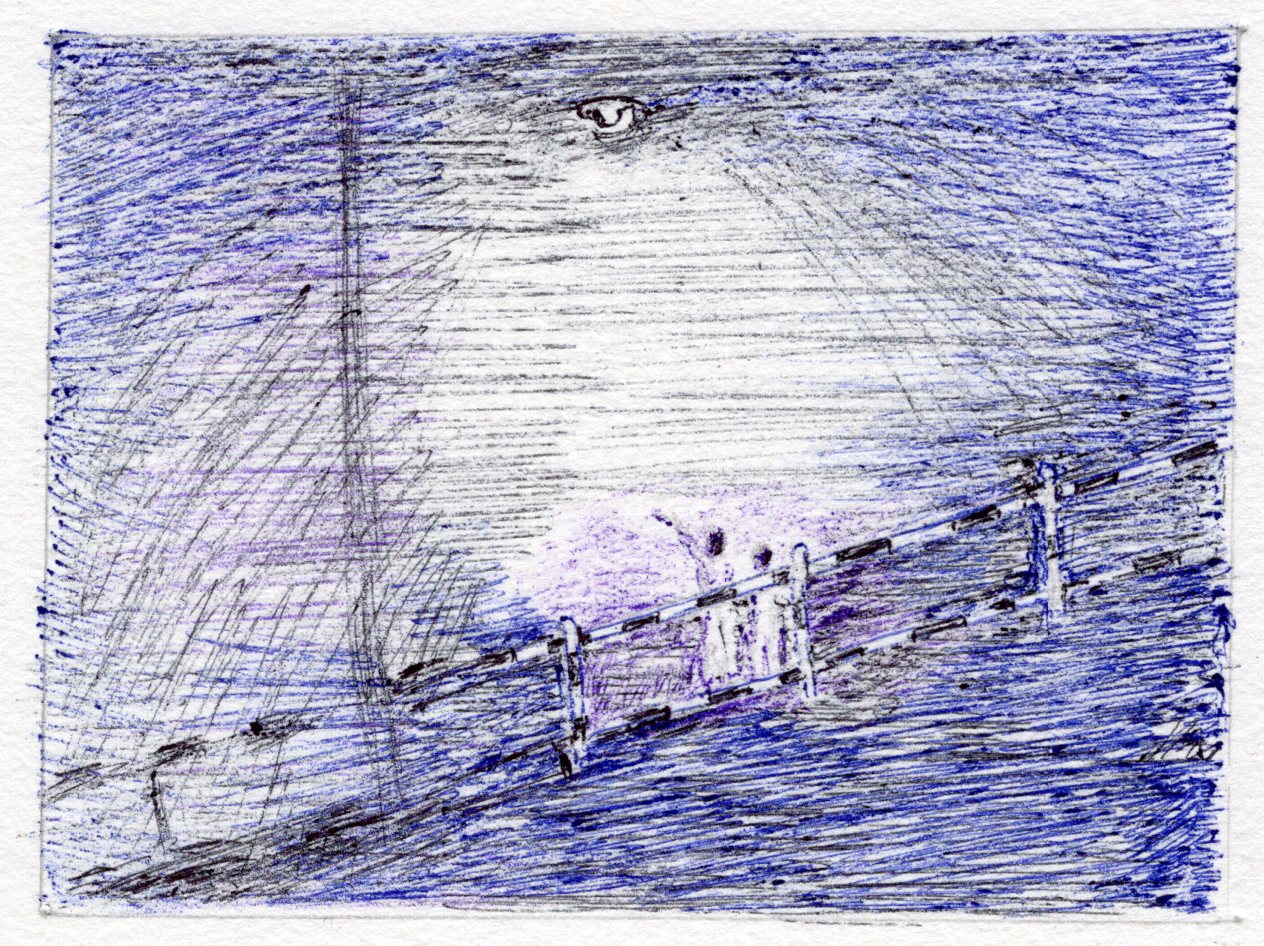

Notice the scene over the bridge. Mostly atmosphere, in dark long shot, with Apu’s recitation presiding.

Feed a poet and he would sing, would be the sub-text of the scene. The world is a beautiful place, Apu would tell you in so many ways. Is he drunk? Yes but not in the way a policeman may object. Still, Ray doesn’t want to take a chance and clears this through Pulu’s comment in the next shot by the railway tracks. Even a misunderstanding on this score would be damaging to the cause of Apu’s character. And the story.

Apu is not interested in the typist’s job that Pulu had in mind for him. He tells him he values his independence far too much for that. Instead his heart is set on being a novelist. When he narrates the plot of what he is working on, Pulu points out that it is his own story. The scene ends with the two arguing about the place of fact in a work of fiction.

Considering that Apu’s own story is being developed towards a sudden, unexpected, quirk-of-fate marriage, it’s easy to see that Ray is setting him up as a carefree artist for maximum impact. The process begins with his lack of interest towards the girl in the window. Curiously, the ‘instrument’ of denial is a flute that he gets from his bookshelf and gently closes the window with. (The flute here is as subtle as Nand Babu’s calendar in Aparajito.) Then he begins to play on the same flute, the first time we see him do that. Next we can see that he is in his elements while reciting poetry, both over the bridge into the night and soon thereafter during the boat ride in the countryside with Pulu. (As a boy, we saw him impress the school inspector with an impassioned recital in Aparajito). He even carries his flute to the village, to Aparna’s house where her mother sees Lord Krishna in him. He has the flute as the villagers approach him for marriage, as indeed when he calls Pulu to tell him about his change of mind about marriage.

The flute lasts until his unattached days. Once married, that’s the end of the flute. As indeed of writing too. His pursuit of arts takes a back seat once Aparna happens to him and it’s given a complete miss after she is no more. Will he ever be able to revive and resume, is one of the open questions at the end of the film.

Notice smoking. There was quite a fuss made about it in Aparajito where he never smoked. In Apur Sansar there is another kind of fuss made about smoking and it begins here.

One of the things he tossed on the bed upon returning—although we don’t see it directly—is a pack of cigarettes and matchbox. Next in the restaurant there’s a cloud of smoke hanging in the air, somebody even blowing a ring as Pulu describes the village they are going to but without either of them smoking. Apu brings out his pack as they are walking along the tracks. Here he lights up when narrating his novel to Pulu. Interestingly, having paid the bills so far, Pulu takes a cigarette from him and begins to listen to his narration.

It’s a friendship among un-equals after all. Both are smoking from the same pack as they indulge in that most friendly banter.

Notice mise-en-scene of this last scene along the tracks.

It’s a pun of sorts that the camera trolley (almost certainly an official line-inspector’s trolley) should be used along tracks that trains run on. In-built in the concept is the danger associated with walking in that zone. After Aparna’s death, Apu comes here to kill himself.

The source of light for this shot, too, is a railway engine standing just round the curve in the distance and suitably blocked by the bridge.

For lighting the two characters, there would be Subroto Mitra’s famous tungsten light bank standing beside the camera on the ample trolly platform.

One detail that’s never been noticed is Apu’s unbuttoned cuff. Right from the time he leaves home for the day, his cuffs have been hanging loose. Perhaps it’s meant to add to his carefree casual manner—’unbound, so to speak—in contrast to, say, his buttoned up collar in Aparajito. That the open cuffs shouldn’t have been noticed means that they work.

And if that be so, we should expect his cuffs buttoned up after marriage. We’d see if that really happens.

Fade out